µ pour corrections

VOIE

MYSTIQUE

I

Sources historiques

Dossier

assemblé par Dominique Tronc

MYSTIQUES

en Terres d’ISLAM

HISTORY

in PERSIA, CENTRAL ASIA, INDIA

HOMMES

DU BLÂME & NAQSBANDIYYA

CONTENUS

Ce

premier

de trois dossiers est

provisoire.

Il assemble des informations en français ou en anglais. Mais

l’essentiel

intime

demeure

caché

.

Ses

informations peuvent éclairer

même

si la

lignée des ‘Aînés’ prit

place au sein de conditions de vie et culturelles si éloignées de

notre culture que leur

méconnaissance

conduit

à des interprétations contradictoires.

Il

risque

de trop

concentrer

l’attention sur l’historique

au détriment de

ce qui demeure d’intérêt universel

en

introduisant

des distinctions secondaires, traces mortes d’un

passé bien oublié.

Mais ses

exemples biographiques

situent

les conditions que nos

aînés ont dû surmonter.

Deux

tomes de sources convergent du cadre général historique au

spécifique vécu intime, procédant ainsi de l’écorce au fruit.

Le troisième et dernier tome est un relevé de témoignages de

mystiques « associés » où une douzaine « d’apôtres »

représentent équitablement, quatre par quatre, trois Traditions

mystiques (à défaut d’une quatrième vivante en extrême-orient

).

Leurs regards sont orientés vers le même Indicible.

J’opère

en succession de zoom ou grossissement (et spécialisation). Voici

leurs contenus des deux premiers tomes :

UNE VOIE MYSTIQUE Tome I.

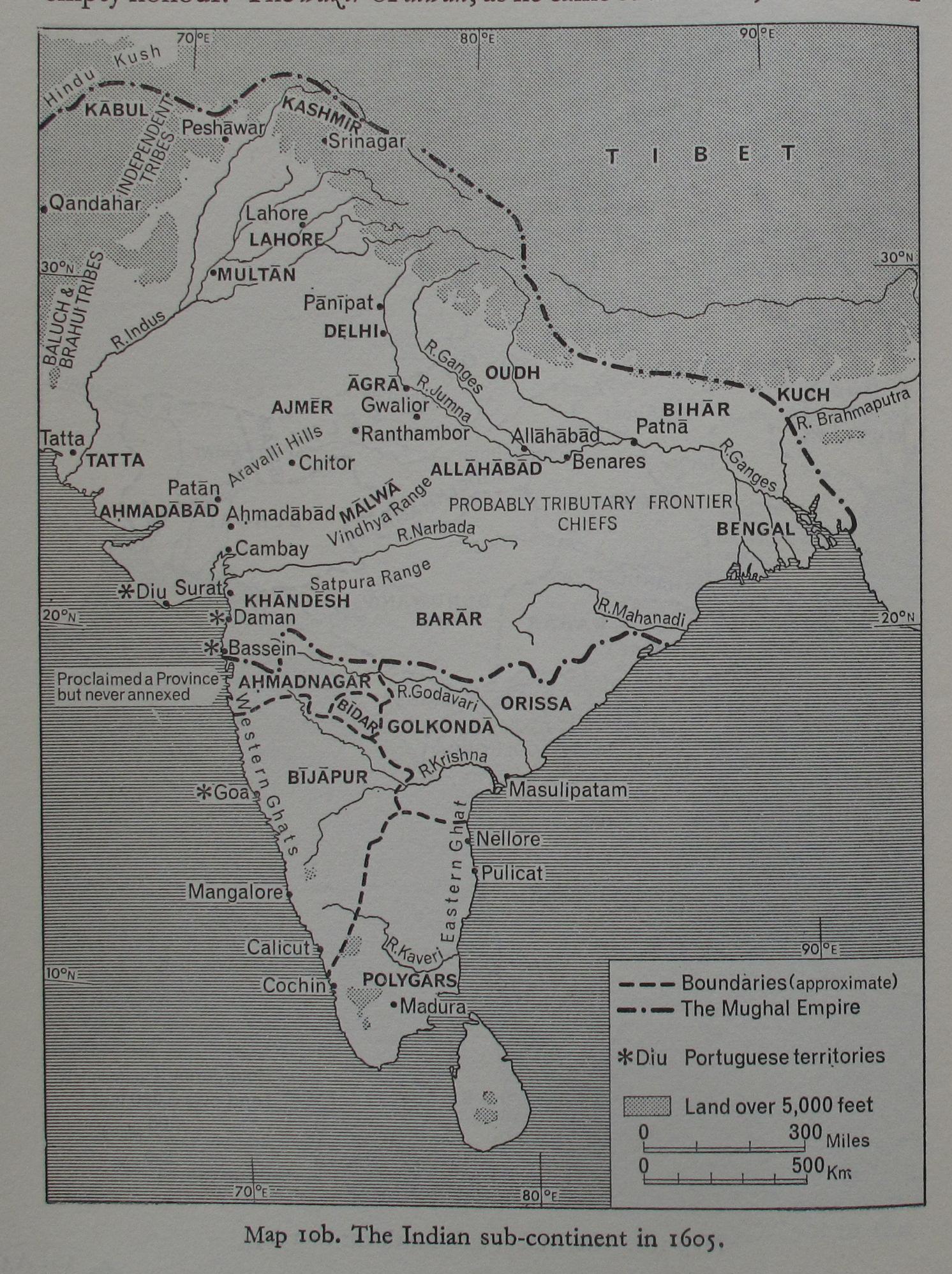

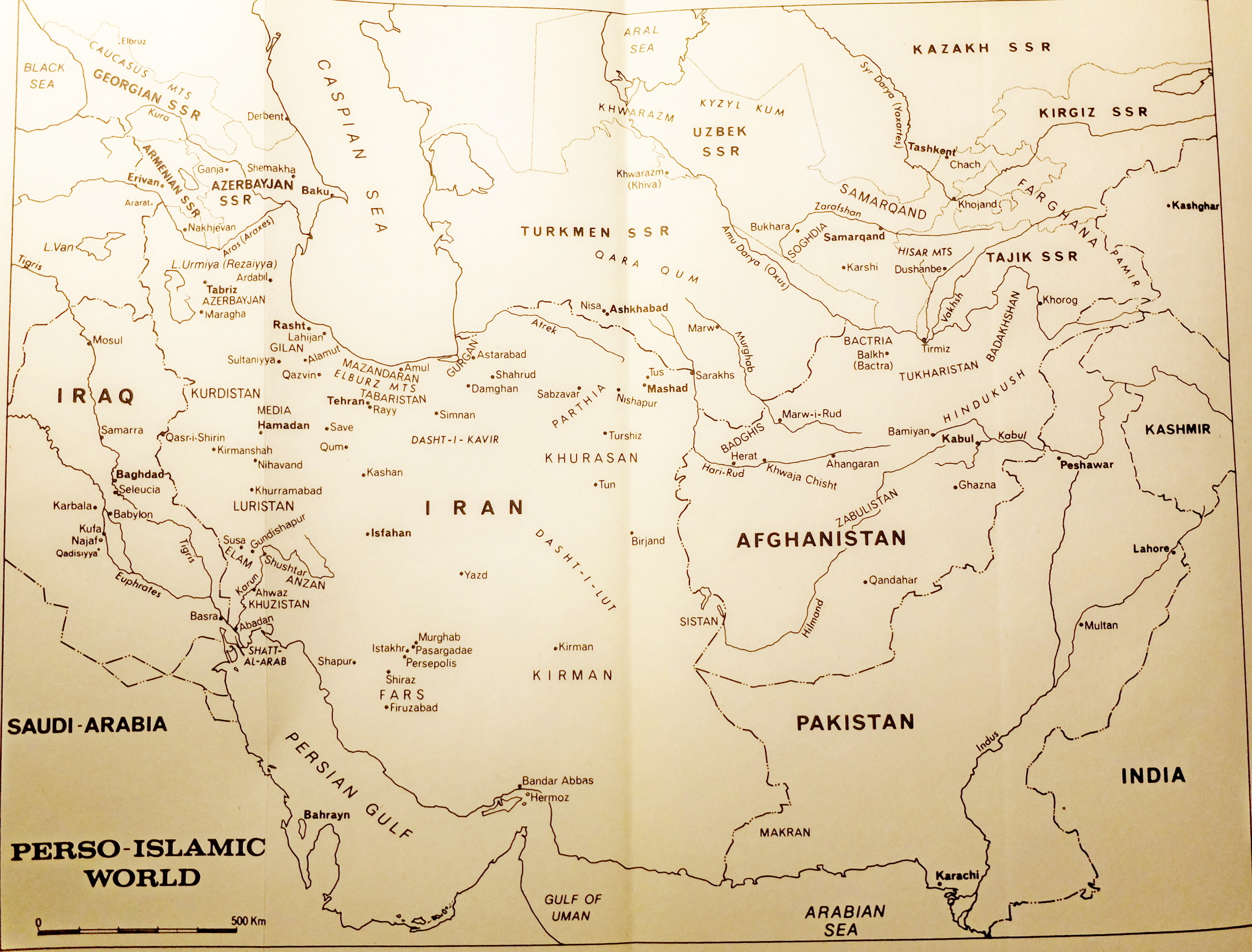

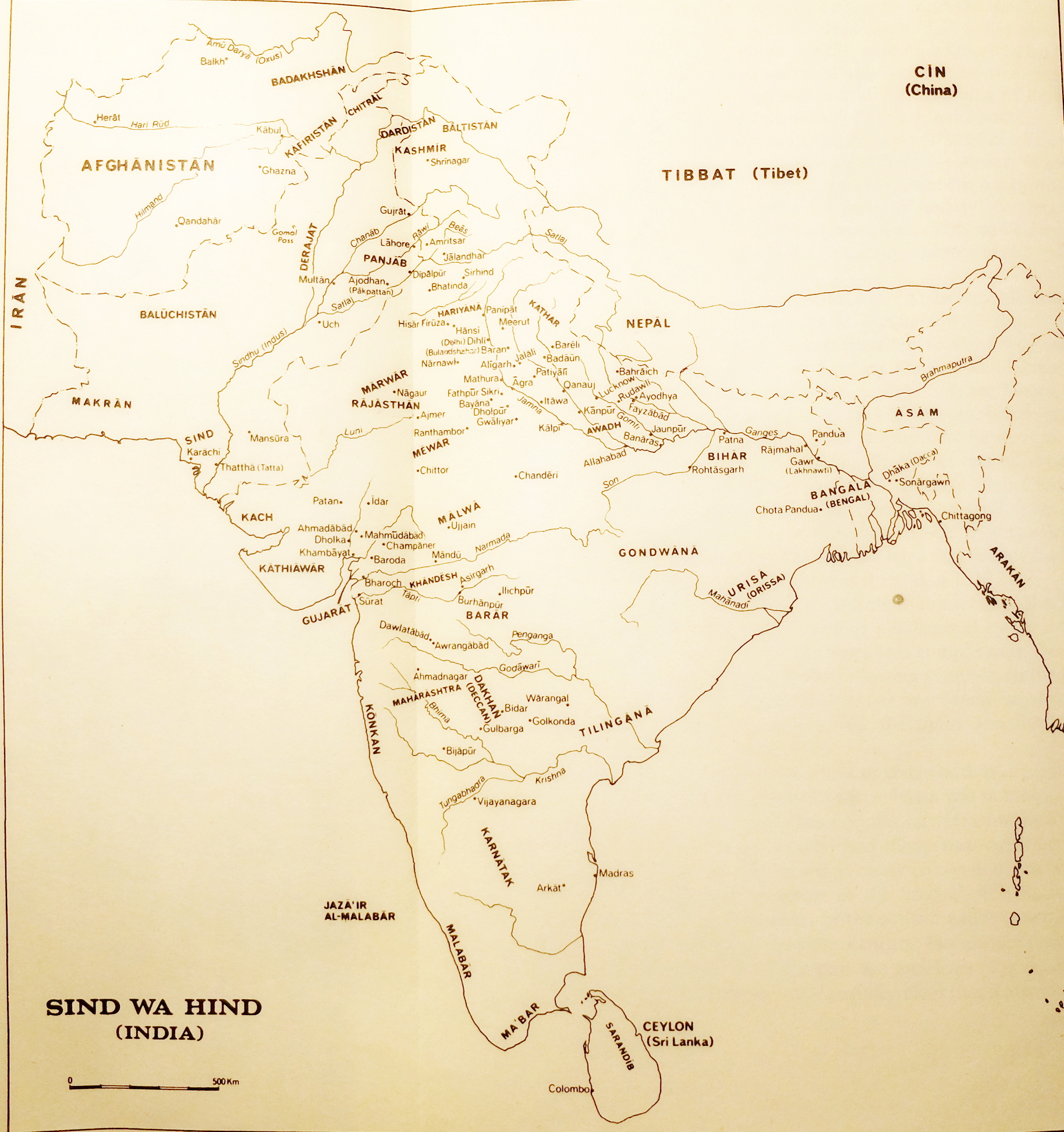

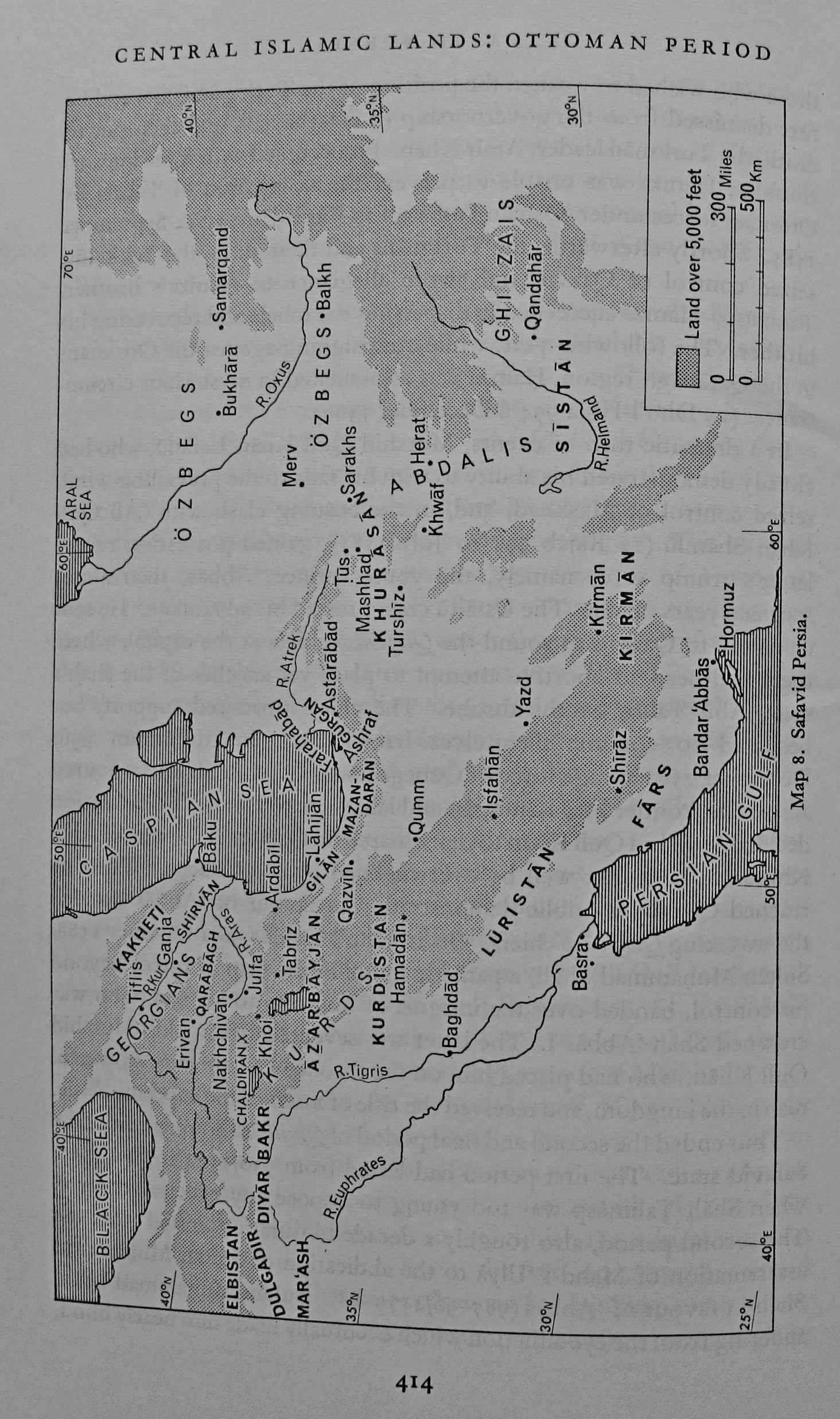

1. MYSTIQUES en Terres d’Islam

ouvre le dossier sur une présentation française large des soufis et

des hommes du blâme

ainsi que d’une synthèse en anglais orientée par

2.

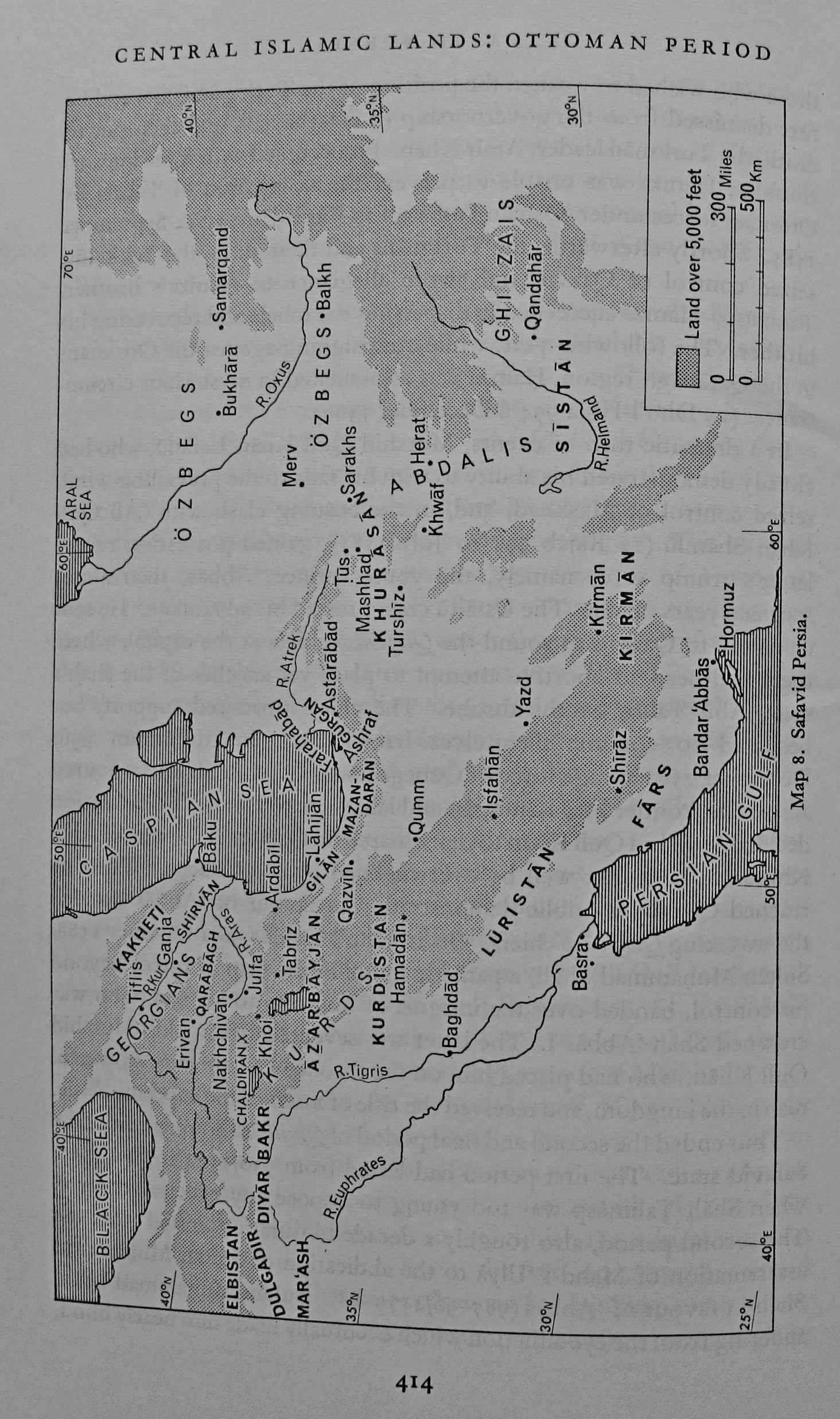

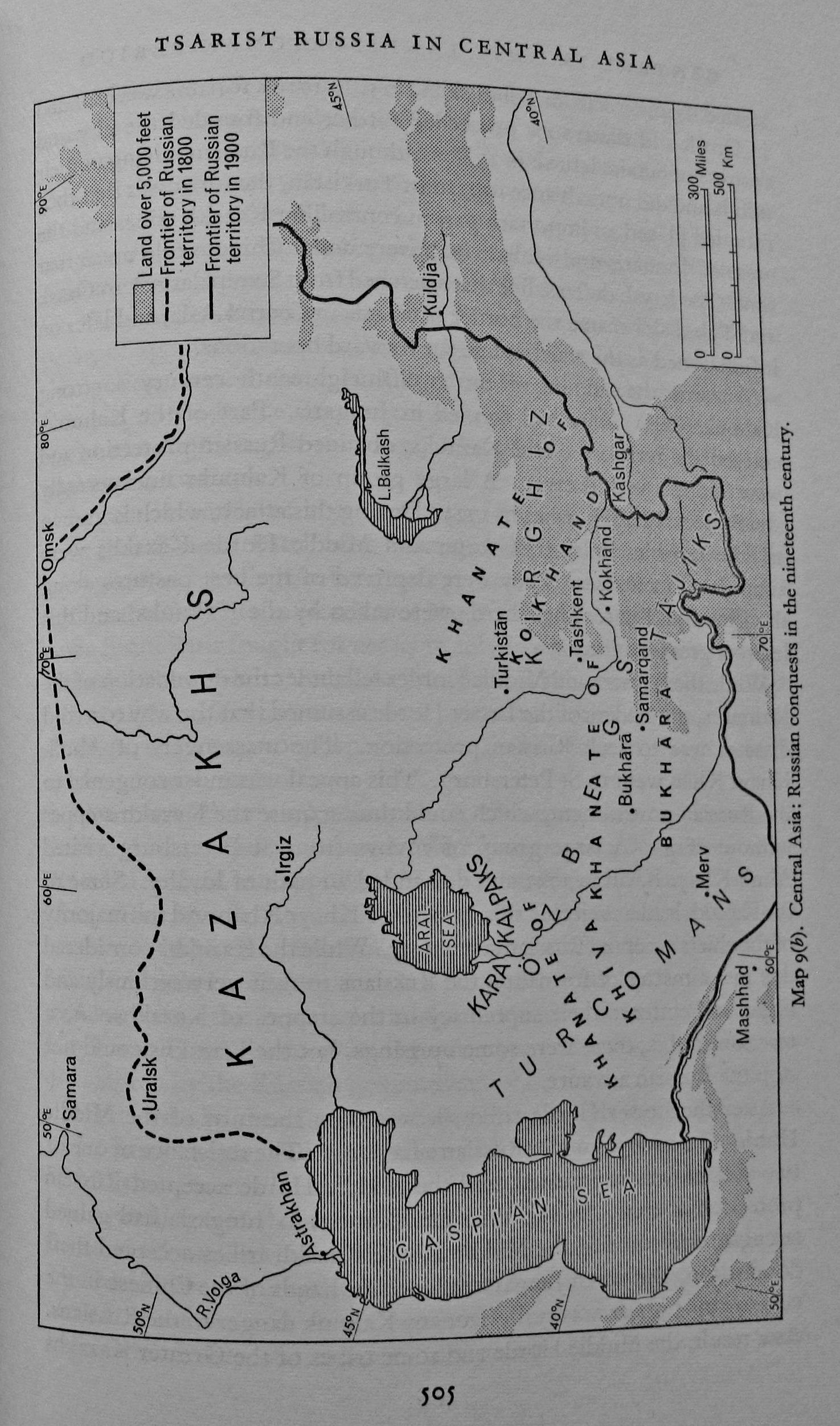

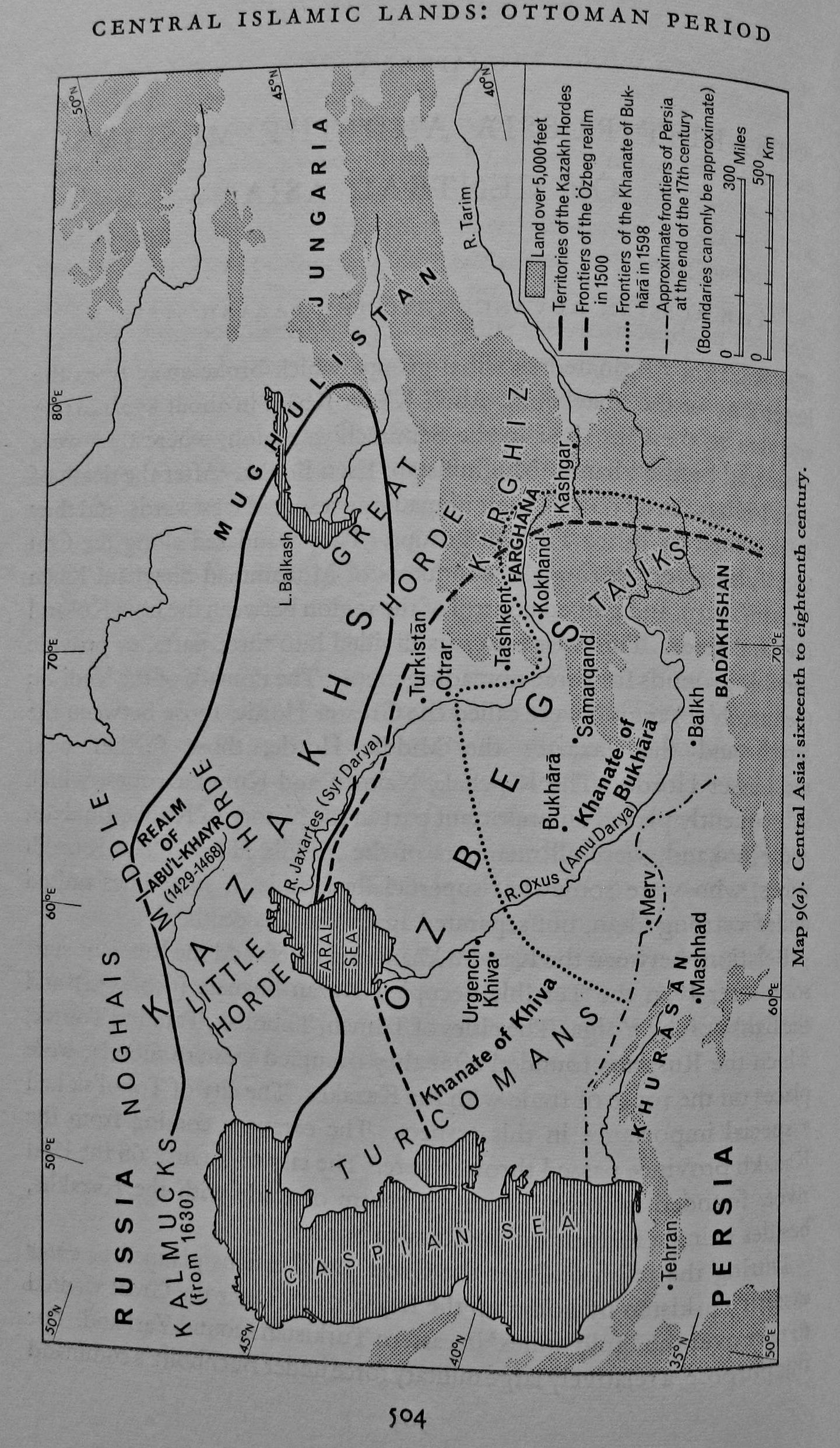

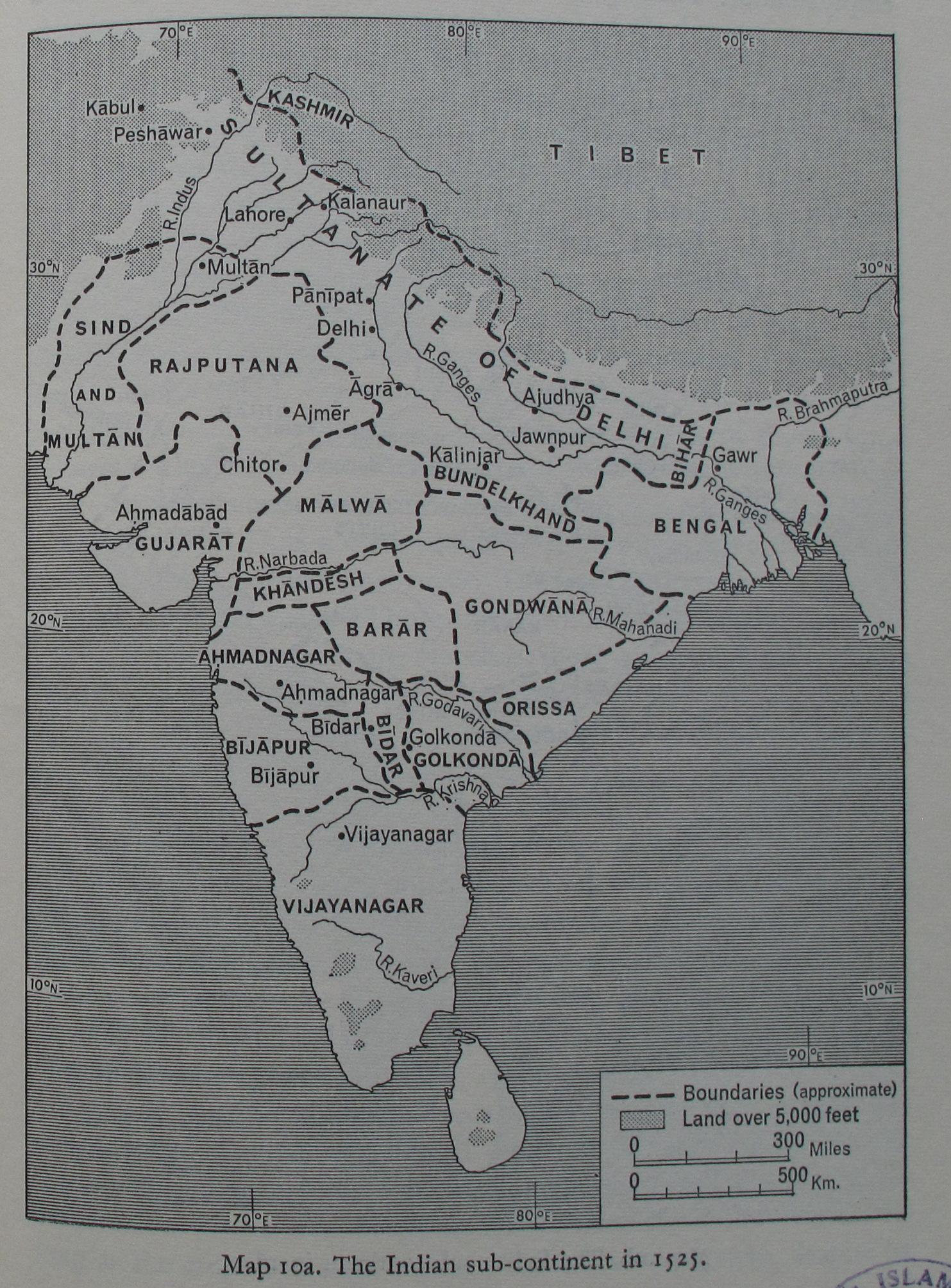

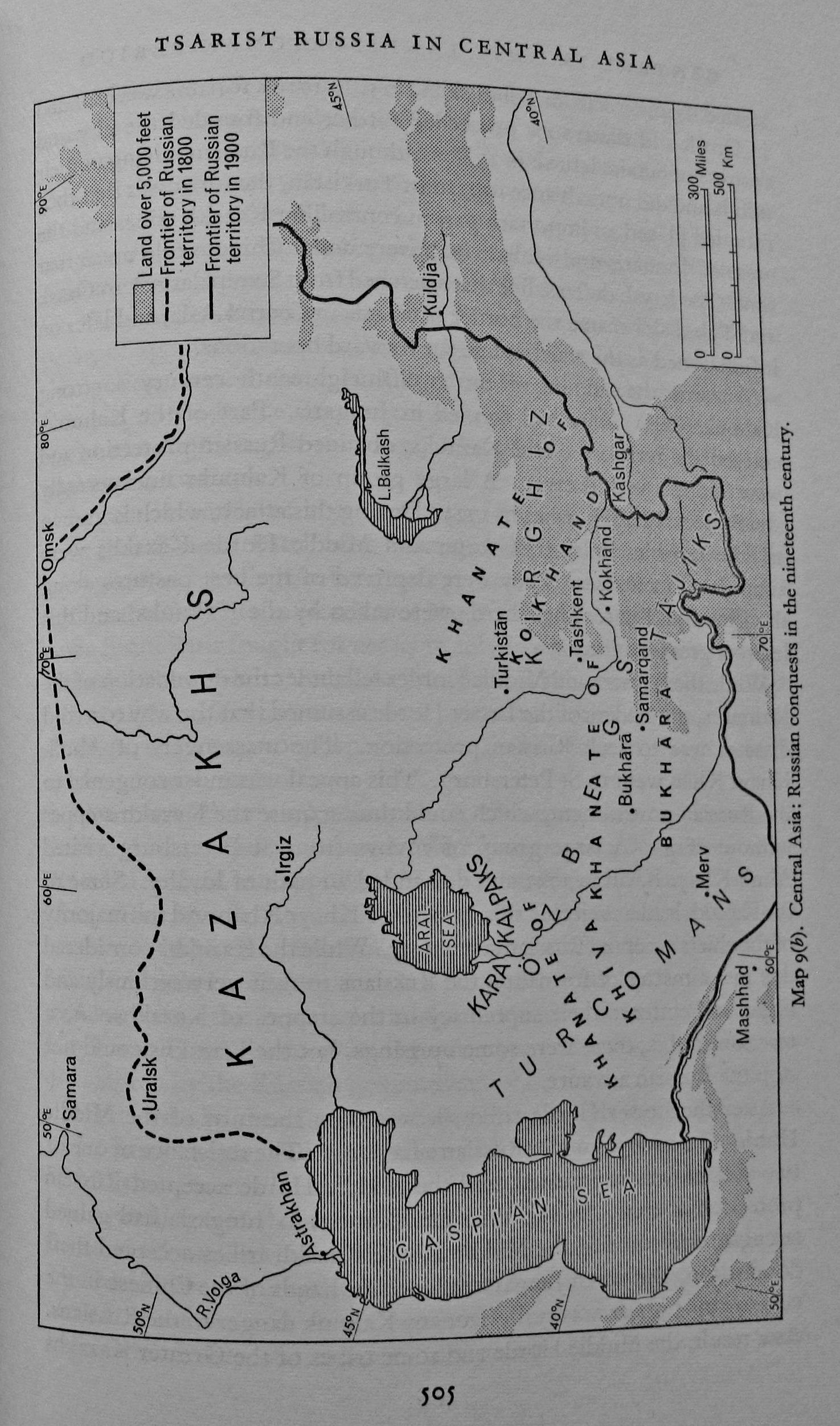

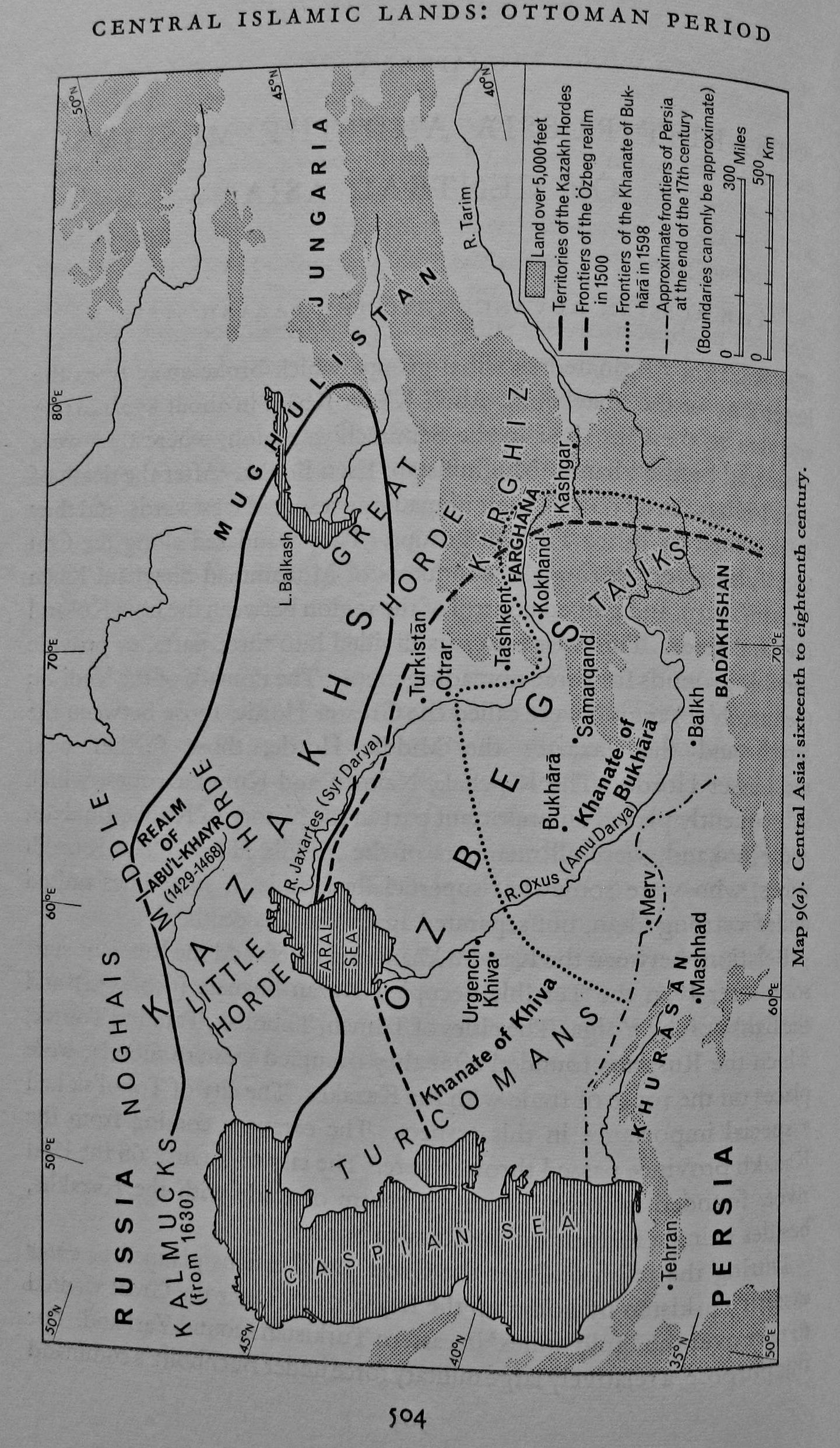

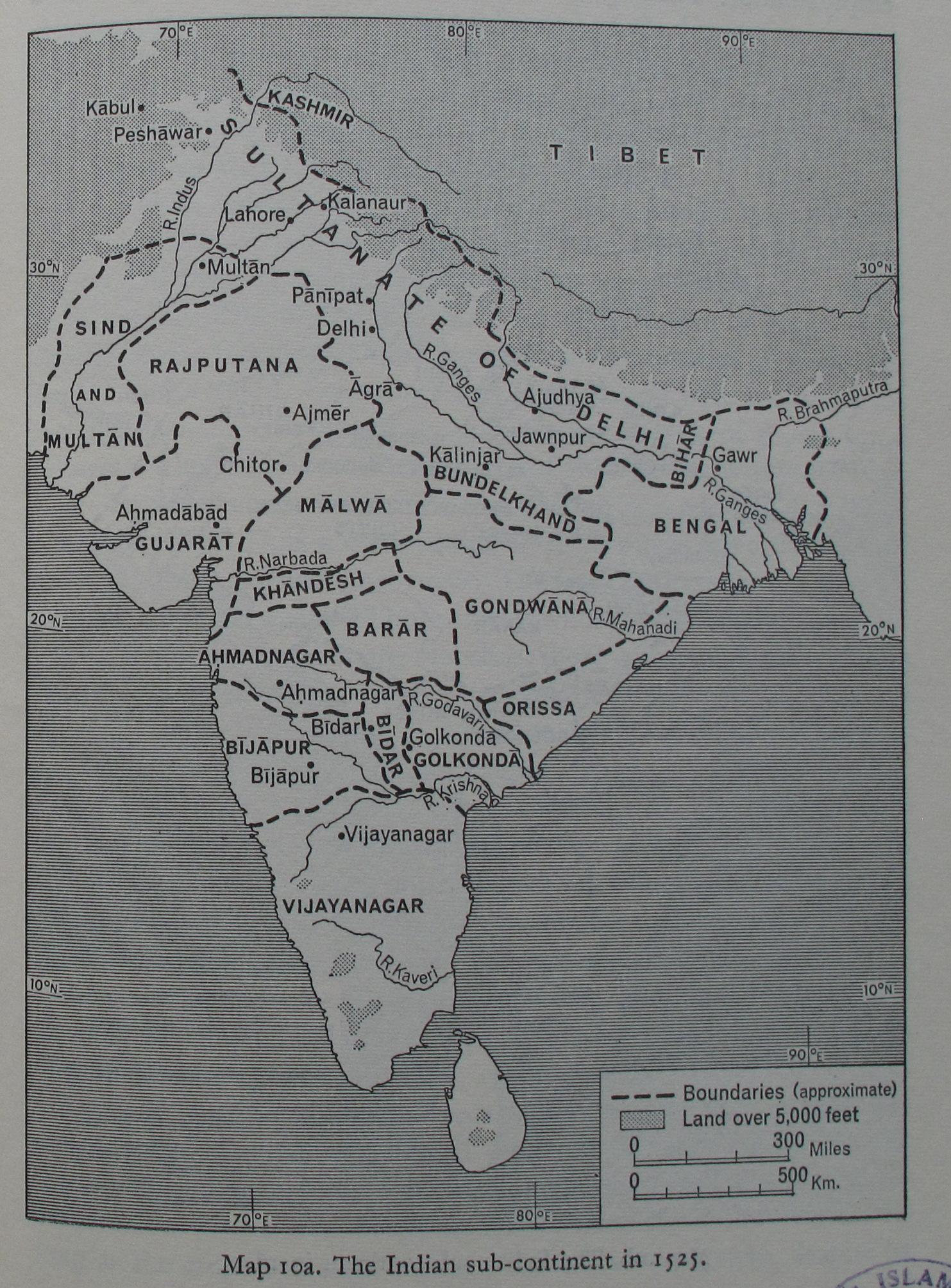

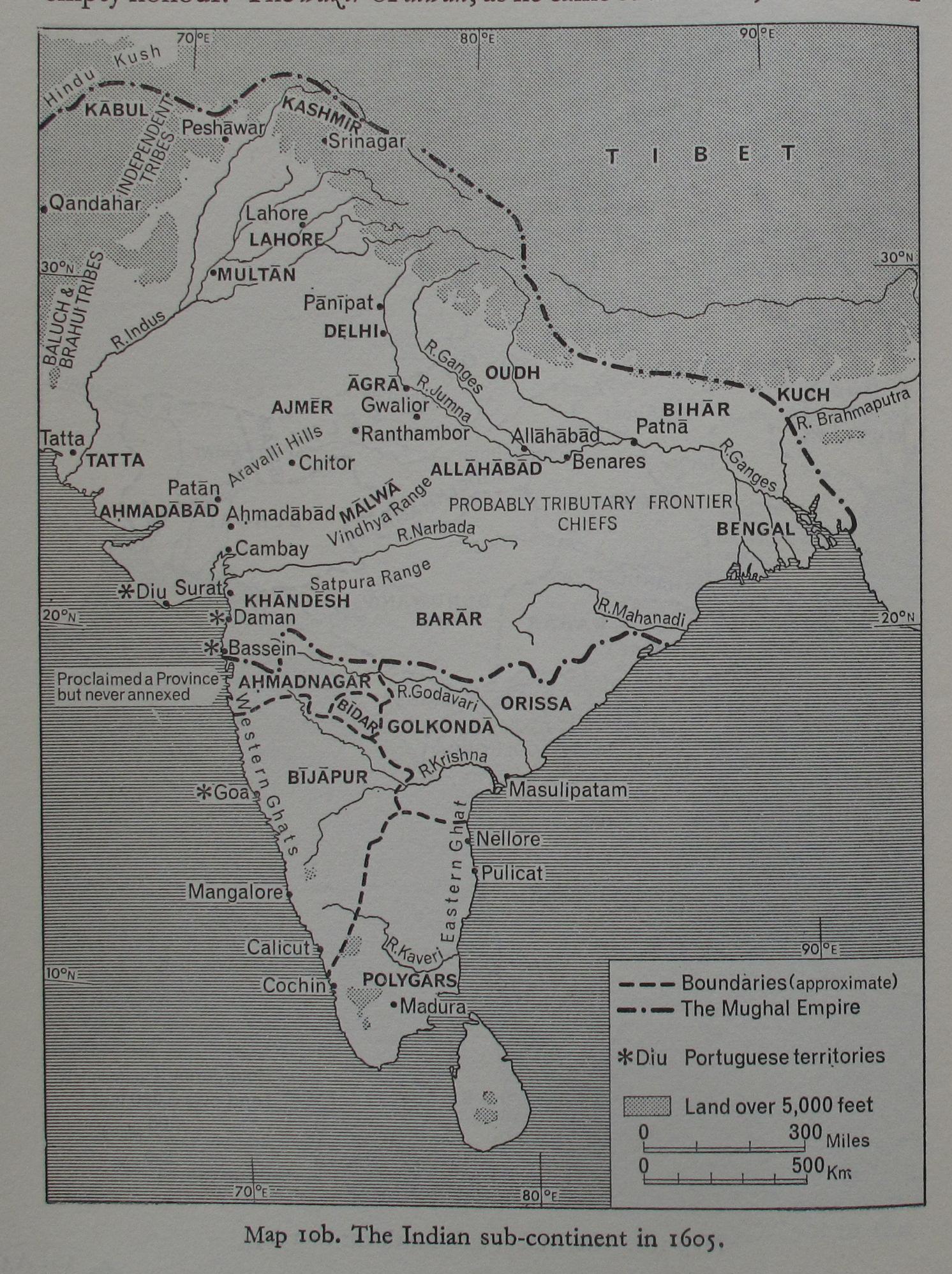

HISTORY in PERSIA,

CENTRAL ASIA, INDIA, introduit à deux grands empires musulmans

nés en Asie centrale.

Cadres

historiques méconnus.

3.

HOMMES DU BLÂME &

NAQSBANDIYYA présente

l’ordre de soufis et d’hommes du blâme du nom de leur

réformateur Naqsband.

UNE

VOIE MYSTIQUE Tome II.

4.

FILIATIONS dont

l’une remarquable mystiquement parmi les nombreuses silsilas

de la Naqsbandiyya vit l’accomplissement intime en une transmission

silencieuse de coeur à coeur.

5.

QUATRE

ÉCRITS ANCIENS :

La

lucidité implacable de Sulamî, Traité de l’amour

d’Ibn ‘Arabi et le Traité de l’Unité qui

lui fut attribué, Les

Jaillissements de Lumière

de Jâmî.

6.

DEUX

MYSTIQUES EN

RELATION :

les rapports

unissant Lilian Silburn à son Maître.

Les

pièces regroupées en six sections sont présentées dans leurs

formes d’origine.

TABLE

LIMITÉE AUX DEUX PREMIERS NIVEAUX

(Consulter

également la Table détaillée figurant en fin de volume)

1.Mystiques 237 pages

2.History 247

3.Blâme Naqs 210

1. MYSTIQUES en Terres d’Islam

Trois tendances parmi les

spirituels qui vécurent en terres d’Islam

– les

soufis : Ils sont attestés à Koufa puis à Bagdad, dans

l’actuel Irak, par des figures marquantes telles que Râb’iâ.

Ils sont liés à la religion musulmane même si certains traits sont

inspirés du monachisme syrien ou indien. Ils se distinguent le plus

souvent par leur mode de vie retirée ou communautaire, en contraste

avec l’existence laïque de milieux urbains fortement socialisés.

Certains s’attachent aux états spirituels et à des pratiques

favorisant l’apparition de transes, ou mieux, le partage d’états

avec ceux de leur maître. Ainsi repérables par leurs vêtements,

leurs règles, leurs monastères, pratiquant l’ascèse, le terme

‘soufi’ devint synonyme de ‘mystique’ en terre musulmane.

Ils

n’ont guère besoin des docteurs de la loi. Par leur pratique

parfois inspirée des prophètes, au point de mettre en question le

rôle totalisant du dernier d’entre eux, Mohammad, ils font

facilement l’objet de persécutions : Hallâj (-922), Hamadâni

(-1131), Sarmad (-1661) et beaucoup d’autres sont les figures

emblématiques martyrisées en pays arabe, iranien, indien. Ils

furent influencés par le modèle présenté par l’avant-dernier

prophète Jésus.

– Les

gens du blâme ou malâmatîya apparurent à Nichapour dans le

Khorassan, province du nord-est de l’Iran. Le premier d’entre eux

serait Hamdun al-Qassâr (-884). Ils se réclament de Bistâmî

(-849) et sont attestés par des figures telles que Sulamî (-1021),

leur premier historien, suivi d’Hujwîrî (-1074), auteur d’un

célèbre traité soufi. Le simple et très direct Khâraqânî

(-1033) fut le premier au sein des directeurs mystiques : le

‘pôle’ de son époque. Tous demeurent cachés, se méfient des

états et rejettent les pratiques, ‘blâmant’ leur moi jusqu’â

son effacement complet. Ils ne sont pas à confondre avec certains

qalandarîya et d’autres excentriques.

– Les

théosophes : une tendance théosophique (au sens premier

du terme, à rapprocher de la théologie mystique telle

qu’elle fut pratiquée par des spirituels chrétiens comme Syméon

le Nouveau Théologien) s’illustre chez Sohravardî (-1191),

Ibn ‘Arabî (-1240), Shabestarî (-1340). Elle est

particulière en Iran chiite, reprenant des éléments de la

tradition sassanide tels que des symboles propres au jeu

lumière/ténèbres, les émanations propres au néo-platonisme

supposant un monde intermédiaire. Elle s’illustre chez Molla Sadra

(-1640) pour devenir un chemin intellectuel (peut-être sous

influence de docteurs du judaïsme médiéval ?).

En

fait on ne doit pas cloisonner les mystiques en terre d’Islam

en plusieurs voies, car elles fonctionnent comme des tendances qui

peuvent s’associer chez le même individu : ainsi Abû

Sa’id (-1049) apparaît-il à la fois soufi et homme du blâme.

Le ‘premier des philosophes’ Abû Hamid al-Ghâzalî (-1111) est

devenu soufi : il est l’auteur du bref Al-Munqid,

‘Erreur et délivrance’, autobiographie spirituelle et témoignage

du grand philosophe éveillé à la mystique

(son frère Ahmad, probablement à l’origine de la conversion du

philosophe, fut un soufi éminent). Ibn ‘Arabî demeure le

‘premier des soufis’, né en Andalousie, mort à Damas,

d’influence immense.

Répartition

des principales figures mystiques

Voici

par régions géographiques les

principales figures d’une foule

innombrable.

Sur les 35 noms retenus, la moitié vivent entre 1000 et 1300, grande

période des civilisations urbaines arabe et perse, finalement

presque détruites par les Mongols (les invasions de Gengis Khan se

situent autour de 1220), auxquels succédèrent des Turco-Mongols

(Tamerlan / Timur exerce ses ravages autour de 1400). Double coup de

hache avant et après des pestes particulièrement meurtrières dans

les villes.

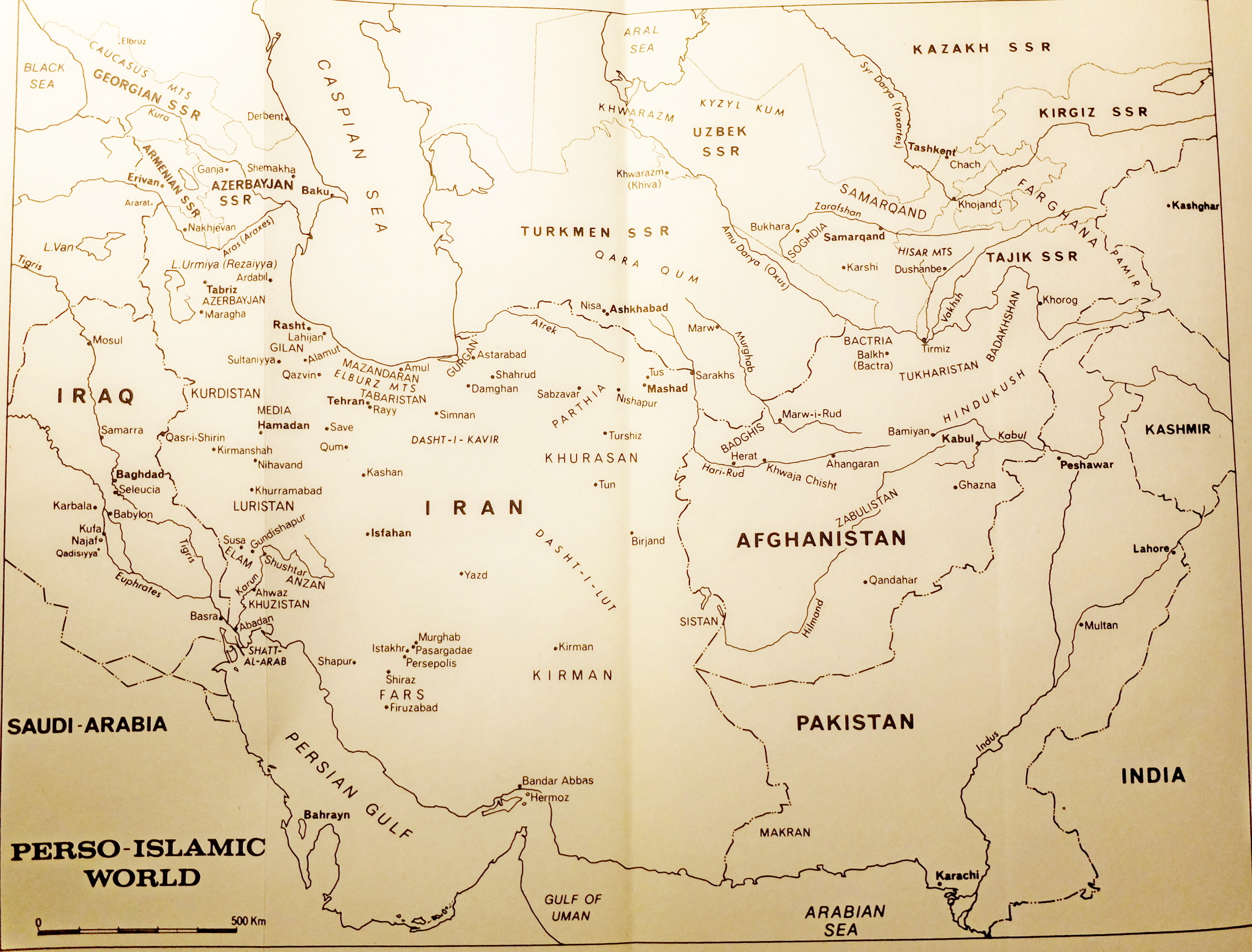

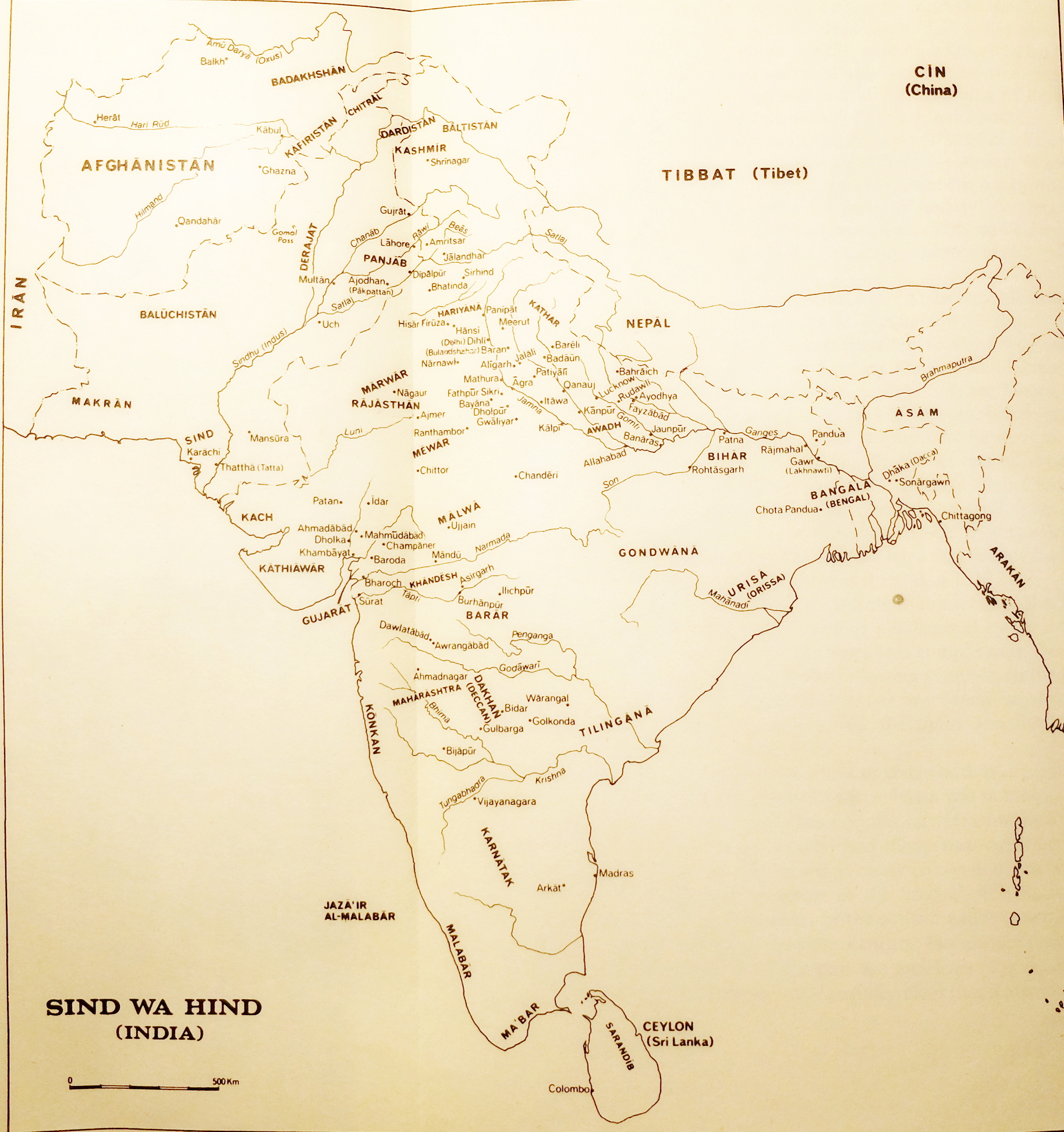

Verso

et page suivante

« CARTE

DES LIEUX » selon des zones réparties en six colonnes de

l’ouest vers l’est et en deux rangées du nord au sud.

On

retient les lieux présumés de naissance et de décès. On

n’oubliera pas la mobilité d’un Ibn ‘Arabî (de Murcie à

Damas !) ou de Ghâzalî le Philosophe (Tus, Bagdad, Damas,

Nishapour, Tus) ou de Jîlî (de Bagdad en Inde ?). Une figure

est alors présente deux fois (lien signalé par un « > »).

Le nom figure en caractères gras au lieu de « séjour »

privilégié.

ANDALOUSIE

Ibn’ Arabî Murcie 1165 >

Ibn Abbad Ronda

1332 >

|

ANATOLIE

Rûmî (1-2)

> Konya

-1273

Sultan Valad (1-2 )

Konya

1226-1318

|

|

MAGHREB

Ibn al-Arîf (3)

Marrakech

?-1141

Ibn Abbad de Ronda (3)

> Fez -1390

|

ÉGYPTE

Ibn al Faridh (3)

Le Caire 1181-1235

|

SYRIE

Sohravardi (4)

> Alep -1168

Ibn ‘Arabi (4)

> Damas

-1240

ARABIE

Nombreux pèlerinages â

La Mecque

|

AZERBAIJAN

( Nord-Ouest de l’Iran )

Sohravardi Azerbaijan 1155 >

Shabestarî (4) Tabriz ?-1340

|

KHORASSAN

( Nord-Est de l’Iran )

Bistâmî

(2) Bastam

777-848/9

Sulamî

(2) Nishapour

937-1021

Kharaqânî

(2) Kharaqan

960-1033

Hamid

Ghâzâli (2) (philos.)

Tus

1058-1111

(&

Bagdad, Damas, Nishapour)

Ahmad

Ghâzâli (2) (sûfî)

Tus

apr.1058-1126

Attâr

Nishapour

1142-1220

Isfarayini

Kasirq

1242 >

Jâmî

Khorassan 1414 >

|

ASIE CENTRALE

(Ouzbékistan, Afghanistan…)

Kalabadhi (1) Boukhara

?-995

Abu-Sa’id

(2) Meyhana

967-1049

Ansari (2)

Herat

1006-1089

Kubrâ Khwarezm

1145-1220

Rûmî Balkh

1207 >

Naqshband

(2)

Boukhara

1317-1389

Jami (2)

Herat

> 1492

|

IRAK

Rab’ia (1)

Basra

?-801

Junayd (1)

Bagdad

830-911

Hallaj (1) Bagdad

> 922

Niffari (1-3) Irak

879-965

Hamid Ghazali (philosophe) à Bagdad

Isfarayini

(2) Bagdad

> 1317

Jîlî Jîl

(Bagdad) 1366 >

|

IRAN

Hallaj Tûr,

FARS

~857 >

Hamadani (1-2) Hamadan

1098-1131

Ruzbehan (4) Shiraz

1128-1209

Nasafi (4)

Iran-sud

?-1290

Saadi (2)

Shiraz

1208-1292

Lahiji (4)

Shiraz

?-1507

Sarmad >

|

INDE

Hujwiri (2)

Ghazna Lahore ?-1074

Maneri (2)

Maner, BIHAR 1263-1381

Jîlî >

Inde?

>1428

Ahmad Sirhindi

(2)

Sirhind, PENJAB

1564-1624 Sarmad

(3) > Delhi

-1661

|

On n’oubliera pas que les entités politiques arabes puis turques

étaient seules en contact avec le monde chrétien : elles ont

fait écran à notre connaissance des mondes musulmans de la Perse,

de l’Asie centrale et de l’Inde, eux-mêmes étrangers et souvent

hostiles aux mondes arabes et turcs .

L’image d’une infinie variété affectant les vécus et les

pensées doit être substituée à la vision mythique d’un « grand

califat » réglé par le seul Coran. Cette variété s’explique

par la situation centrale des régions concernées, constituant un

carrefour si on la compare à l’excentrement et au relatif

isolement d’une presqu’île européenne chrétienne avant sa

domination maritime, d’une péninsule indienne, d’une plaine

chinoise protégée des zones civilisées par des déserts brûlants

ou glacés. Nous distinguons plusieurs appartenances ou groupes

: (1) à prédominance soufie, (2) à prédominance marquée par les

« hommes du blâme », (3) non classés dont des mystiques

d’Afrique du nord, (4) influencés par une théosophie.

Les

mystiques musulmans (Marijan Molé)

AVERTISSEMENT

Le présent livre

ne prétend pas être une histoire du soufisme ; son format ne le

permettrait pas, et il n'est pas encore possible de l'entreprendre.

Trop de textes importants restent inédits et trop de facteurs nous

échappent. Notre but a été d'en présenter les grandes lignes et

de suggérer, sur certains points, la voie dans laquelle le

développement de recherches nous paraît devoir être fructueux.

Mais nous ne donnons pas de solutions aux problèmes abordés.

Notre

présentation suit le cadre chronologique, mais sans rigidité. Là

notamment où l'examen d'un problème général à propos d'un

mystique nous paraissait l'exiger, nous n'avons pas hésité à

poursuivre le développement et à anticiper sur l'époque suivante.

D'autre part, aux différentes époques, nous avons concentré notre

attention sur quelques problèmes qui se sont posés aux soufis,

l'influence chiite et la réaction sunnite, l'expérience mystique et

la doctrine de l'être. Sur ce dernier point, nous croyons avoir

donné une interprétation nouvelle, mais qui aura besoin d'une

élaboration plus poussée dans un travail plus technique. Ce

problème permet également d'entrevoir une liaison plus grande et

plus intime entre la théorie et la pratique soufies, entre la méta-

2

physique

de l'être, la conception de l'extase mystique et la coutume du samâ

cette liaison étant fondée sur la représentation du « Covenant »

primordial.

Ceci

nous a conduit à consacrer quelques développements au samâ, mais

nous n'en donnons pas une description exhaustive. Nous n'analysons

pas non plus la Voie soufie, ses pratiques, ses rites, ses

institutions. Ces problèmes seront traités ailleurs.

CHAPITRE

PREMIER LA PRÉHISTOIRE

Le

mysticisme islamique présente pour l'observateur européen des

difficultés considérables. La difficulté intrinsèque de

comprendre une religion étrangère n'est pas la moindre. A quel

point m'est-il possible de connaître une expérience religieuse,

individuelle par définition, qui non seulement n'est pas la mienne,

mais encore se développe à l'intérieur d'un système dont les

coordonnées ne me sont pas familières ? L'entreprise exige un

effort considérable ; tout en restant lui-même, le chercheur doit

se mettre dans la situation de ceux qu'il étudie et suivre leur

expérience de l'intérieur.

Les

difficultés que présente l'islam sont d'un autre ordre que celles

auxquelles nous avons affaire en abordant les religions de l'Inde ou

de l'Extrême-Orient, nées dans un milieu culturel qui n'a eu, avec

celui d'où est sortie notre civilisation, que des rapports

sporadiques et extrêmement lointains. Sur ces domaines, avant de

pénétrer dans l'univers de ces religions, un Occidental doit

d'abord s'approprier un langage conceptuel dont il sait d'avance

qu'aucun terme ne recouvre exactement la valeur de celui qui, dans sa

propre langue, a une acception voisine ; et

4

que

tout le système des références et la hiérarchie de valeurs sur

quoi ce langage est fondé diffèrent profondément de ceux auxquels

il est habitué.

Le

cas de l'islam est différent. La plus grande partie des éléments

dont est bâti son système religieux sont les mêmes que ceux qui

entrent dans la structure des systèmes juif et chrétien, tandis que

la philosophie islamique dérive en grande partie des mêmes sources

que la scolastique médiévale ; la mystique musulmane continue, en

partie, les traditions des mystiques hellénistique et chrétienne.

Mais ces éléments communs n'ont ni la même valeur ni la même

place dans le système islamique que dans le système chrétien.

L'islam n'est pas un christianisme imparfait, ni le christianisme un

islam imparfait ; chacune de ces deux religions a une structure sui

generis qui se suffit à elle-même et dont les différents

éléments doivent être compris et jugés selon les critères qui

lui sont propres.

Ces

réflexions valent notamment pour le problème si controversé des

origines du soufisme. Sa théorie contient plusieurs éléments qui

sont connus d'autres religions et les pratiques soufies évoquent,

plus d'une fois, certains usages analogues des moines chrétiens ou

bouddhistes. Mais les soufis n'ont jamais voulu être autre chose que

des musulmans ; toutes les doctrines qu'ils professent, et tous leurs

gestes, coutumes et usages, s'appuient sur une interprétation du

Coran et de la tradition prophétique. Il y a là deux plans à

distinguer. Dans leur intention, les soufis ne font autre chose que

méditer sur la révélation coranique et pratiquent, avec ferveur,

le culte musulman. Mais, au moment de la conquête arabe, la

population du Proche-Orient professe d'autres religions et ne

s'islamise que progressivement ; la masse des musulmans au début de

l'époque abbasside est constituée par les convertis chrétiens,

mazdéens, manichéens, etc. En adoptant la nouvelle religion

dominante, ces hommes n'ont pas, du jour au lendemain, oublié leurs

traditions ni changé leur façon de penser. L'influence du substrat

religieux préislamique sur l'islam dans la période formative de ce

dernier ne s'est pas exercée uniquement par contact direct entre

théologiens chrétiens et conquérants arabes, mais aussi par la

persistance, au-delà du changement de credo, de certaines formes

sociales et de certaines structures qui s'insèrent désormais dans

un contexte nouveau et y retrouvent un sens nouveau.

La

tradition sur Salmân Farsî, « le barbier perse », ou Salmân-i

Pâk « le barbier pur », a ici la valeur d'un symbole. Fils d'un

mage, Rôzbih douta de la religion de ses ancêtres et partit à la

recherche du vrai prophète. Il se fit tout d'abord moine chrétien ;

puis, familier de Muhammad, il accepta sa religion, et devint son

client et son compagnon, voire son confident. Le Prophète aurait dit

à son sujet : « Salmân fait partie de nous, gens de la maison »,

et cette phrase, comprise comme le prototype de l'adoption

spirituelle et de l'initiation, joua un grand rôle dans l'ésotérisme

islamique. Confident de ‘Ali, il se serait opposé à l'élection

d'Abû Bakr au califat ; d'autres traditions, visiblement sunnites,

en font par contre un confident d'Abû Bakr, et son disciple : et

c'est à ce titre qu'il est revendiqué comme ancêtre spirituel par

certaines congrégations sou fies. Il serait mort

6

à

Madá'în, l'ancienne Ctésiphon, capitale de l'empire des

Sassanides. On montre en tout cas sa tombe, objet de pèlerinage, non

loin des ruines de cette ville.

Quelle

que soit la réalité historique qu'ils recèlent, les récits sur

Salmân ont une valeur de symbole : le barbier perse, le client

‘adjami admis dans la famille prophétique, le patron de petits

artisans qui peuplent depuis des temps immémoriaux les bazars des

grandes villes du Proche-Orient, ne représente-t-il pas ces milliers

de mawâli non arabes, dont l'adhésion à l'islam permit à

ce dernier de surmonter la tentation de n'être qu'un autre judaïsme,

une religion réservée aux conquérants arabes, et de s'épanouir

pleinement comme une religion universelle qui ne connaît pas de

barrière de race ? Son adhésion à la nouvelle foi est entière et

sa sincérité ne saurait être mise en doute. Mais, né mazdéen,

converti au christianisme, Salmân a-t-il tout oublié de son passé

au moment où il devient musulman ?

Voyons

la carte religieuse des pays où va se former la nouvelle

civilisation : la Perse, l'Iraq, la Syrie et l'Égypte à la veille

de la conquête arabe. Des cultes anciens subsistent ici et là, mais

la plus grande partie du territoire en question a été soumise au

double nivellement hellénistique et chrétien ; ceci apparaît

immédiatement pour sa partie occidentale, politiquement romaine,

mais la double empreinte est sensible également dans l'Empire perse.

La résistance des anciennes religions est inégale ; rien ne

subsiste plus de celle de l'ancienne Égypte, du paganisme grec, des

cultes syriens. Les Harraniens se rattachent sans doute beaucoup plus

à la philosophie néoplatonicienne qu'à ces derniers. Seule des

anciennes religions nationales, le mazdéisme est encore vivant. Le

christianisme a pourtant pénétré dans l'Empire perse ; malgré les

persécutions, l'Église nestorienne de Perse est majoritaire parmi

la population araméenne de l'Iraq et son activité missionnaire la

porte en Iran proprement dit, en Transoxiane et, au-delà, jusqu'en

Chine.

A la

veille de la conquête, la Perse n'est donc pas exclusivement

mazdéenne. Le mazdéisme, d'autre part, n'est pas homogène. Il

vient de traverser une crise qui a laissé de profondes blessures et

amené la naissance d'une nouvelle religion, le mazdakisme. D'une

façon générale, l'attraction spirituelle du mazdéisme est épuisée

et sa vitalité religieuse bien entamée. Lorsque les mystiques

persans parleront de la « taverne des mages » et se

proclameront « mazdéens », il s'agira uniquement d'un « chiffre »

pour « mauvaise religion », ce qui n'implique ni contact direct,

ni, à plus forte raison, influence du mazdéisme sur la mystique

islamique.

A

l'époque qui nous intéresse, les provinces orientales de la Perse

sont bouddhistes. Il est très malaisé de discerner ici les

influences possibles. Certaines analogies peuvent s'expliquer par une

parenté élémentaire. Le chapelet est d'origine indienne, certains

détails du costume soufi peut-être également. La légende

d'Ibrâhim Adham est bien d'origine bouddhique, mais son modèle

direct, le Roman de Barlaam et Budasaf, a été transmis par

les manichéens d'Asie centrale. Quoi qu'il en soit, des survivances

bouddhiques sont a priori possibles ; il n'en est pas de même de

prétendues infiltrations védântines. Dans la période formative de

la civilisation islamique, on

8

voit

mal leur assise territoriale. L'essai récent de retrouver du Védânta

chez Abû Yazid Bistâmî doit être considéré comme un échec.

Les

manichéens sont nombreux. Aux premiers siècles de l'islam, ils

représenteront un danger réel pour la nouvelle religion et la

polémique contre eux sera à la fois acerbe et féconde. Des

infiltrations manichéennes dans le soufisme sont possibles ; la

désignation fréquente de saints soufis comme des siddîqîn

peut continuer un usage manichéen. Il n'y a pas lieu, en revanche,

de tirer de conclusions précises du fait que des soufis ont été

accusés, ici ou là, d'être zindîk. A cette époque, ce

terme désigne certes avant tout les manichéens, mais aussi, par

extension, tous ceux qui sont, de quelque façon que ce soit,

suspects à l'orthodoxie islamique ; l'accusation est on ne peut plus

ambiguë.

D'autres

sectes gnostiques doivent subsister : les mandéens de nos jours en

offrent un échantillon. Certaines de ces sectes se rattachent plus

ou moins au christianisme. Des judéo-chrétiens doivent survivre en

bordure du désert arabe. Les juifs sont disséminés à travers tout

le territoire et forment des communautés importantes en Iraq, en

Perse, en Égypte et en Syrie.

C'est

pourtant le christianisme qui occupe la place la plus importante. Les

controverses christologiques du Ve siècle ont brisé

l'unité de l'Église officielle. L'Église de Perse est nestorienne,

celles d'Arménie et d'Égypte, la plus grande partie de celle de la

Syrie byzantine, celle d'Éthiopie, sont, au contraire, monophysites.

Persécutés par les empereurs, les monophysites accueilleront les

Arabes comme libérateurs ; un essai de compromis, presque

contemporain de la conquête, n'aboutira pas à sauver la situation,

mais amènera la naissance d'une troisième Église syriaque,

l'Église maronite. Face aux monophysites et aux nestoriens, les

partisans du concile de Chalcédoine sont beaucoup moins nombreux.

Étroitement unis à la Grande Église de Constantinople, ils sont

connus sous le nom de melkites, « les impériaux ».

Ces

différences dogmatiques ont pour nous ici beaucoup moins

d'importance que certains phénomènes, certains traits de structure

qui sont communs aux trois Églises en question : le monachisme et

l'ascétisme extrêmement puissants et vigoureux, aussi bien en

Égypte que dans les pays de langue syriaque, et à l'intérieur de

ce monachisme, certains mouvements et courants de pensée hétérodoxes

qui présentent des analogies frappantes avec certains courants

soufis ; je pense en premier lieu à l'origénisme et au

messalianisme.

Le

monachisme syriaque se distingue de son homologue égyptien par

plusieurs traits notables. A l'époque la plus ancienne, nous avons

affaire à une organisation d'ascètes libres, vivant parmi les

autres, et ne se distinguant d'eux que par des pratiques ascétiques,

supplémentaires et, notamment, par la continence absolue. Ces

ascètes, benai qeyâmâ « fils du covenant », vivent en

mariage spirituel avec des vierges ascètes. Plus tard, lorsque aura

prévalu une organisation ecclésiastique analogue à celle des

communautés grecques, l'institution des benai qeyâmâ

disparaîtra, mais non sans laisser de traces. La phase suivante

du monachisme syriaque est formée, comme en Égypte, par

l'anachorétisme ; finalement, le cénobitisme prévaut, comme

ailleurs.

10

L'ascétisme

syriaque se signale par des mortifications exceptionnellement rudes ;

les performances des stylites sont connues, et elles ne sont pas

isolées. Dans des cas limites, le mépris de la chair pouvait aller

jusqu'à la mort volontaire dans les flammes. La pauvreté était

considérée comme une vertu, et l'ascète parfait abandonnait tout

ce qu'il possédait pour se confier entièrement à Dieu. La vie

errante en était le corollaire fréquent.

Ne

possédant rien, n'ayant pas où poser sa tête, sale, vêtu de

loques, le moine errant était un pneumatique. Alors que son

apparence extérieure semblait devoir l'exposer au mépris de tous,

il atteignait des états mystiques élevés et, notamment,

contemplait des visions spirituelles.

Un

des phénomènes caractéristiques de cette mystique est l'apparition

d'ascètes qui, par leur comportement extérieur, font tout pour

s'attirer le blâme de leurs semblables. Ils se comportent de façon

que les autres les croient les pires des hommes : leur coeur est pur

et ils ont tout abandonné pour Dieu, même leur réputation.

On

connaît la captivante histoire que rapporte, au milieu du VIe

siècle de notre ère, le monophysite Jean d'Éphèse dans le

chapitre 52 de ses Vies des saints orientaux. Le narrateur,

Jean d'Amide, a vu dans sa ville deux jeunes gens qui se comportaient

comme des bouffons, plaisantaient avec tout le monde et recevaient

des coups. Le garçon portait le costume d'un mime, la fille celui

d'une courtisane. Les grands de la ville voulaient l'enfermer dans un

lupanar, car personne ne savait où les deux jeunes gens passaient la

nuit. Le garçon déclara alors que la fille était sa

11

femme et la sauva ainsi ; une dame pieuse voulut s'occuper d'elle,

mais n'arriva pas à percer le secret du couple. Or, Jean se mit à

les observer et finit par les voir prier la nuit. Après lui avoir

fait jurer de ne trahir à personne leur véritable état, ils lui

confièrent leur secret. Ils s'appelaient Théophile et Marie et

appartenaient à de nobles familles d'Antioche. Lorsque Théophile

eut quinze ans, son père lui ordonna un jour d'aller à la campagne.

Il se rendit à l'écurie pour prendre quelques chevaux. Il vit alors

des rayons de lumière qui sortaient de l'écurie. Il s'approcha et

regarda à travers le trou de la porte : un pauvre homme se tenait

debout sur le fumier et priait, les mains tendues vers le ciel. Des

rayons de lumière sortaient de sa bouche et de ses doigts. Théophile

se jeta aux genoux de l'inconnu et lui demanda de lui confier son

secret. C'était un Romain, nommé Procope, d'une famille de

notables. Avant que son père le mariât, il avait tout abandonné et

commencé une vie errante qui l'avait amené jusqu'en Orient. Si

Théophile a vu des rayons de lumière émaner de lui, c'est que Dieu

veut son salut. Avant un an, ses parents et ceux de Marie mourront.

Ils abandonneront la fortune qu'ils auront reçue en héritage, se

consacreront uniquement à Dieu et adopteront un déguisement sous

lequel personne ne pourra les reconnaître. Aussi longtemps qu'ils le

garderont, ils pourront gagner de grands mérites et vivre une vie

spirituelle. D'autre part, aussi longtemps qu'il ne lui témoignera

aucune marque de respect, et qu'il le laissera tel qu'il est, au

milieu du fumier, Théophile pourra le voir ; sinon, il s'en ira et

il ne le reverra jamais. Tout se passa comme l'avait dit Procope ;

après la mort

12

de

leurs parents, Théophile et Marie abandonnèrent tout, se

consacrèrent entièrement à Dieu et se déguisèrent en bouffons.

C'est ainsi que, priant en secret, gardant une chasteté absolue, ils

s'exposent toute la journée au blâme et au mépris des hommes.

Théophile répète ici à son interlocuteur la mise en garde que

Procope lui avait adressée : aussi longtemps qu'il ne leur

témoignera aucune marque de respect, qu'il ne les traitera pas, en

public, autrement que les autres, il pourra les revoir. Sinon, ils

disparaîtront et il ne les reverra jamais.

Pour

la préhistoire de la mystique islamique, ce récit est intéressant

à plusieurs égards. Retenons-en deux. Des saints vivent parmi les

hommes, inconnus et méprisés. Personne ne les reconnaît comme

tels, ils ne se révèlent qu'à des élus, destinés à mener la

même vie qu'eux et à atteindre la même perfection. C'est, à

l'état embryonnaire, la conception qui sera à la base de la

représentation soufie d'une hiérarchie invisible d'Amis de Dieu qui

passent leur vie ignorés de tout le monde, mais sans lesquels le

monde ne pourrait exister.

Le

second aspect est étroitement lié au premier. C'est l'idée de la

sitûtâ, « mépris », « blâme » : non seulement le saint

parfait doit mener une vie qui ne permette pas aux autres de deviner

son état, mais il se fait même insulter, passe pour un fou (satê),

se considère comme le pire de tous et agit en conséquence. Ce sera

le principe même des malâmatîya islamiques.

Un

des documents les plus curieux de la littérature mystique syriaque,

les plus controversés aussi, le Livre des degrés (Ketâbâ

de-masqâtâ),

donne une justi-

13

fication

doctrinale de ce comportement. En bref, il s'agit d'une imitation

parfaite du Christ. Le parfait a tout abandonné, il n'a pas où

poser sa tête. Il s'est confié entièrement à Dieu et vit dans la

chasteté absolue. Il se considère comme le pire des hommes, se mêle

à tout le monde, est « tout avec tous », sans juger personne.

Ayant renoncé à tout, il ne pense qu'à Dieu. L'Esprit Saint, le

Paraclet, vient habiter en lui et il retrouve la perfection qu'a

possédée Adam avant sa chute.

Cette perfection n'est pas le fait de tous les chrétiens dont le

Ketâbâ demasqâtâ

distingue deux catégories les justes (kênê ou zaddîqê) et

les parfaits (gemîrê). L'Écriture contient deux sortes de

prescriptions : celle de la justice et celle de la perfection. Les

faibles, qui sont comme des enfants, doivent suivre les premières,

qui sont pour eux comme le lait maternel. Ils pardonneront à leurs

ennemis, donneront des aumônes, prendront une seule femme, éviteront

le contact des méchants et observeront certaines prescriptions

alimentaires. C'est la loi seconde, celle qui fut donnée à Adam

après sa chute. Mais les parfaits vivront une vie purement

spirituelle. Ils aimeront tout le monde, ami ou ennemi, entreront

partout et seront « tout avec tous ». Ayant tout abandonné, ils ne

donneront pas d'aumônes visibles — puisqu'ils ne possèdent rien

—, mangeront tous les aliments et observeront une chasteté

absolue. La loi de la justice suffit pour le salut posthume ; mais

seule l'observation de celle de la perfection permet d'obtenir

l'inhabitation de l'Esprit Saint et d'atteindre, après la mort, un

degré plus élevé.

Une

conception métaphysique spécifique est à

14

l'arrière-plan

de cette distinction. Dieu a créé deux mondes, le monde visible et

le monde invisible ; le premier n'est que le symbole du second. Il y

a de même deux églises : l'église visible et l'église spirituelle

invisible. La première, qui est comme une éducatrice, est le

symbole de la seconde. Ses rites, ses sacrements, sont l'image de

sacrements spirituels : le baptême visible est nécessaire, mais il

n'est que l'image du baptême spirituel qui seul confère la

perfection et dont le résultat est la venue du Paraclet. Les

parfaits tiennent d'ailleurs fermement à l'église visible et à son

ministère : elle est comme un chemin qu'il faut nécessairement

emprunter, mais qui ne suffit pas.

Les

rapports qu'établit le Livre des degrés entre le monde

visible et le monde invisible, entre les sacrements de l'Église

catholique et les sacrements spirituels, sont, compte tenu des

différences de climat religieux, exactement superposables à ceux

que le soufisme et les sectes shiites extrémistes reconnaissent

entre le zâhir et le bâtin, entre la lettre de la Loi

et la vérité profonde des choses.

On

sait que le Ketâbâ de-masqâtâ

passe en général pour refléter les doctrines des messaliens. Ce

nom syriaque — auquel correspond le nom grec d'euchites — désigne

la secte d'après la pratique qui paraît la plus caractéristique,

la prière perpétuelle, qui seule, au dire des hérésiographes,

permettait de chasser du coeur de l'homme le démon qui y habite à

la suite du péché originel. Il s'agit d'un mouvement ascétique,

répandu dans tout le Proche-Orient mais plus particulièrement en

Syrie et en Mésopotamie, entre le IVe et le IXe

siècle de notre ère. Condamnés par le

15

concile

d' Éphèse (431), les messaliens ne nous sont connus que par les

notices de leurs adversaires, ainsi que, probablement, par deux

documents : les Homélies du pseudo-Macaire (que l'on restitue

maintenant au messalien Syméon de Mésopotamie) et le Livre des

degrés. La divergence la plus importante entre ces écrits et

les notices des hérésiographes porte sur l'appréciation du rôle

de l'Église visible et de ses sacrements. Alors que le Livre des

degrés l'exalte et insiste sur la nécessité de la pratique

extérieure, les messaliens, selon leurs adversaires, mépriseraient

l'Église et estimeraient que la pratique de ses sacrements ne peut

ni nuire ni profiter ; ils assisteraient en conséquence aux

cérémonies de l'Église, mais sans leur attacher d'importance.

Cette affirmation peut n'être qu'une déformation malveillante de la

première. D'autre part, le messalianisme n'a sans doute jamais formé

une secte organisée ; il s'agissait bien plutôt d'un courant

d'idées parmi les moines. Des nuances de pensée, des divergences

d'attitude sont possibles. Certains messaliens ont pu estimer que la

vie sacramentelle de l'Église constituait une propédeutique

nécessaire à la vie spirituelle ; d'autres, qu'elle était dénuée

de toute valeur intrinsèque.

Cette

attitude continue, en fait, celle que le christianisme paulinien a

adoptée envers la loi de Moïse. Seulement, les prescriptions de

l'Ancien Testament et les sacrements de l'Église tels le baptême et

l'Eucharistie sont mis sur le même plan. La confusion a été

d'autant plus facile que — le Livre des degrés en fait foi

— le christianisme syriaque avait dû garder, aux premiers siècles,

une partie des pres-

16

criptions

et des coutumes juives, notamment dans le domaine alimentaire. Il

importe de souligner ici l'importance des paroles de saint Paul sur

l'insuffisance des oeuvres que n'accompagne pas la charité : le

Ketâbâ de-masqâtâ

appelle en effet la loi de la perfection également « la loi de la

charité (hubâ) ».

Le

prolongement islamique est le seul qui nous intéresse ici. Très

tôt, la distinction de deux catégories d'Amis de Dieu commence à

s'imposer. Un des plus anciens théoriciens du soufisme, Muhammad ibn

‘Alî al-Tirmidhî (mort en 285 h.), connaît deux sortes d'awliyâ

: le walî selon le sidq Allâh, « justice ou loi

de Dieu », et le walî selon la minnah, l'action de

grâce. Le premier observe scrupuleusement et laborieusement la Loi

révélée, ce qui lui permet d'échapper à la damnation et d'avoir

une place au paradis. Le second ne désire que Dieu. Il pratique,

certes, les obligations de la Loi, mais il est libre et, dès cette

vie, transcende sa condition individuelle : le Trône du Seigneur

s'installe dans son coeur et il jouit de la contemplation. C'est à

son propos que Tirmidhî commente le célèbre hadîth selon

lequel Dieu devient la vue, l'ouïe, la main, le coeur de ceux qu'il

aime et qui se sont rapprochés de lui.

Or,

un reproche fait aux messaliens est qu'ils prétendaient voir Dieu de

leurs yeux. Le Livre des degrés permet de nuancer : lorsque

l'Esprit Saint est installé dans l'âme du parfait, il voit Dieu

dans son coeur comme dans un miroir. Pour arriver à cet état, il

faut s'y préparer par la prière, le jeûne, les pratiques

ascétiques. Mais la perfection n'est pas automatiquement assurée,

Dieu seul la donne : on peut parfois

17

passer

des dizaines d'années à pratiquer l'ascèse sans jamais atteindre

la perfection.

D'autres

témoignages parlent d'apparitions, de photismes ; le phénomène

n'est pas limité au messalianisme, mais ce dernier semble lui

attacher beaucoup de prix. En réfutant les messaliens, Diadoque de

Photicée essaie de réduire la portée de ces manifestations. On

leur reproche de rechercher des visions, d'en faire le but même de

la vie mystique, de croire que la prière perpétuelle seule amène

infailliblement les états mystiques. Le reproche est injustifié si

l'on se rapporte au Livre des degrés ou aux Homélies

du pseudo-Macaire ; mais un reproche identique sera formulé à

l'encontre des soufis, celui de rechercher l'extase pour elle-même

et de la provoquer artificiellement et notamment par la pratique du

dhikr, « souvenir » ou « mention » de Dieu, la répétition

inlassable d'un nom de Dieu.

Ce

qu'était la prière perpétuelle des messaliens, nous l'ignorons.

Nous savons, par contre, qu'une pratique analogue à celle du dhikr

musulman était (ou plutôt est) courante chez les mystiques

chrétiens orientaux : la prière monologistos, le souvenir de

Dieu (mnêmê Theou) ou de Jésus. Elle est connue plusieurs

siècles avant la naissance de l'islam : Nil, Cassien, Diadoque de

Photicée, Jean Climaque, les hésychastes en portent témoignage.

Mais la liaison de ces pratiques avec des exercices respiratoires

n'est positivement attestée, aussi bien chez les moines chrétiens

que chez les soufis, qu'à une époque beaucoup plus tardive, où des

influences venues d'Extrême-Orient sont possibles en islam, d'où

elles ont pu rayonner sur le christianisme byzantin. Ces

18

techniques

s'insèrent dans des contextes théologiques différents de part et

d'autre ; la pratique de la « mention » du nom divin est justifiée

par des références scripturaires propres à chacune des deux

religions. Le but du dhikr est de purifier l'âme, de la vider

entièrement de la pensée de tout ce qui n'est pas Dieu ; sa

pratique est accompagnée de visions de lumières et d'autres

phénomènes semblables — dont la description est analogue chez les

hésychastes et les soufis —, mais ni chez les uns ni chez les

autres il ne s'agit d'un moyen court, d'une technique amenant

infailliblement et en vertu de ses qualités intrinsèques jusqu'à

l'union à Dieu, ainsi que le leur reprochent leurs adversaires. Ce

reproche sera repoussé aussi bien par Grégoire Palamas que par les

théoriciens soufis.

Un

dernier point commun entre les messaliens et les soufis, mais dont il

est très difficile de connaître quelque chose de précis, la danse.

Une danse sacrée paraît avoir été pratiquée par des messaliens

dont l'un des noms était celui de Choreutes. Selon Théodoret

de Cyr, au Ve siècle, ils se réunissaient pour sauter,

en se vantant de sauter par-dessus les démons. Saint Jean de Damas

connaît une secte d'Hicètes qui se réunissent dans des monastères,

récitent des hymnes et dansent. Une danse en règle est attestée

pour les méléciens d'Égypte, mais il ne s'agit pas là de

messaliens. Faut-il y voir le modèle des séances de sama’

si répandues parmi les derviches musulmans et dont les exemples

classiques sont la danse des Mawlawîya (« derviches

tourneurs ») et celle des ‘Isawîya (« Aïssaoua ») du

Maroc ?

Quoi

qu'il en soit de ce dernier point, les quelques ressemblances entre

les conceptions messaliennes et soufies nous paraissent dignes

d'intérêt. C'est notamment la distinction des deux classes établie

par le Livre des degrés qui est proche de celle que nous fera

connaître le mysticisme islamique ; et, tout comme dans l'écrit

syriaque, la classe des parfaits sera caractérisée par leur sitûtâ,

les plus parfaits des Amis de Dieu étant ceux qui acceptent la

malâma, le blâme. La distinction entre une Église visible

et une Église invisible est directement liée à cette

classification ; mais, dans le Ketâbâ de-masqâtâ, elle

n'implique pas une interprétation ésotérique de l'Écriture,

réservée aux parfaits. Cette interprétation sera très répandue

en islam, comme elle l'avait été dans la littérature patristique.

Si donc connexion historique il y a, ce n'est pas le messalianisme

qu'il faut nécessairement invoquer comme intermédiaire.

Cette

méthode d'exégèse de l'écriture fut pratiquée avec le plus

d'ampleur par les néoplatonistes chrétiens d'Alexandrie, Clément

et Origène. Solidaire d'une philosophie mystique, elle se répandit

dans le monachisme chrétien d'Égypte et du Proche-Orient. Dans

l'islam, elle fut pratiquée aussi bien par les soufis que par les

différents courants shiites, en particulier les ismaéliens. Le

Coran lui-même fournit quelques précédents : les histoires des

prophètes anciens n'y sont pas rapportées par intérêt historique,

mais comme préfigurations de la carrière de Muhammad, de ses

épreuves et du châtiment de ses ennemis. La plus ancienne exégèse

ésotérique du Coran, notamment chez les ismaéliens, suit d'assez

près les mêmes lignes que la typologie patristique. Les soufis,

eux, chercheront à fonder leur spiritualité

20

sur

une exégèse mystique des versets coraniques, les rapportant aux

événements intérieurs de l'âme. La typologie ne sera pas oubliée

; tout comme, depuis Philon jusqu'à Grégoire de Nysse, les

mystiques chrétiens et juifs ont vu dans la vie de Moïse le symbole

de l'itinéraire de l'âme vers Dieu, les soufis considéreront la

vie, la carrière et l'oeuvre de différents prophètes comme des

manifestations de différents attributs divins, attributs dont la

somme se reflète dans l'image de l'Homme Parfait, l'Homme Intégral,

en qui Dieu se contemple comme dans un miroir.

Le

but de l'ascèse est, chez les moines chrétiens, la gnose, cette

connaissance supérieure et intuitive qui conduit à l'union avec

Dieu où qui équivaut à celle-ci. Cette gnose n'est pas

nécessairement hétérodoxe et c'est sans doute beaucoup plus à la

gnose au sens où l'entendent les moines égyptiens qu'à la gnose «

classique » que se rattache le concept soufi de la ma’rifa

qui, pareillement, doit résulter d'une ascèse rigoureuse.

Ascèse

et visions, mystique intellectualiste et gnose, disparition de

l'homme dans l'Un indifférencié au terme de l'ascension, ces

concepts jouent un grand rôle dans la doctrine de l'origéniste

Évagre le Pontique dont l'influence fut grande. Bien que condamnées,

ses doctrines furent pour une bonne part conservées, en partie en

grec, mais beaucoup plus en traduction syriaque et arménienne. Ceci

concerne notamment son principal ouvrage, les Centuries

gnostiques, dont la version intégrale vient seulement d'être

retrouvée et publiée, mais qui ont agi surtout sous une forme

remaniée. D'autres ouvrages d'Évagre ont été également répandus

dans l'Orient syriaque et des fragments de son Antirrhétique

ont été retrouvés en sogdien. Ce dernier fait est particulièrement

important, puisqu'il montre que l'influence origéniste s'est exercée

au-delà même des frontières orientales des territoires qui

devaient devenir le centre de la civilisation islamique dans sa

période formative.

Chez

les Syriens occidentaux, le représentant le plus connu de la

mystique hétérodoxe fut Étienne bar Sudailê, auteur présumé du

Livre d'Hiérothée chez qui l'influence origéniste est très

sensible. L'ascension de l'âme, à travers l'identification avec le

Christ souffrant, aboutit chez lui à une complète identification

avec l'intellect universel. A travers le Dieu Premier, cette

identification vise la Déité indifférenciée et supérieure à

tout.

Origénisme

et messalianisme se rejoignent dans la dernière grande floraison de

la mystique nestorienne, au ler siècle de l'islam, dont

les rapports avec la mystique musulmane devraient être examinés de

plus près. Les deux mouvements vivent longtemps en symbiose. Peu à

peu, la direction des échanges s'intervertit : elle ira désormais

de l'islam vers le christianisme. Ce dernier perd progressivement sa

prépondérance numérique et intellectuelle. Au IVe ou Ve

siècle de l'hégire, des chrétiens se mettront à l'école des

musulmans. A l'époque mongole, le dernier grand nom de la

littérature syriaque, le maphrien jacobite Grégoire Barhebraeus,

dans ses écrits mystiques, s'inspirera directement de Ghazali.

22

NOTE

BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE [excellente et complète, ici omise]

CHAPITRE

II LES ORIGINES

Plus

qu'une doctrine, l'islam est une règle de vie. La vie quotidienne

d'un musulman est marquée par une série d'obligations strictes dont

l'accomplissement scrupuleux lui garantit le salut dans l'autre monde

et le désigne comme membre de la communauté islamique : profession

de foi ; prière, cinq fois par jour, la face tournée en direction

de la Kaaba ; jeûne du mois de ramadan ; aumône légale ;

pèlerinage de La Mecque.

Cette

discipline forme le cadre de la vie d'un musulman. Loin d'être vide

de sacré, celle-ci en est pleine. Contrairement à ce qu'on dit très

souvent, l'islam n'est pas un déisme rationnel, un pur monothéisme

sans clergé ni sacrements. Pour le croyant, il est une loi révélée

qui doit être acceptée dans sa substance et dans sa forme, sans

qu'il en demande le pourquoi, bi-lâ kaifa. Il l'assume telle

qu'elle est et se soumet à la volonté inscrutable de Dieu qui l'a

donnée : il est un muslim. Ce caractère gratuit de l'islam,

l'absence d'explication rationnelle de ses prescriptions, rassure le

fidèle : sa religion vient d'un Dieu qui fait ce qu'il veut, dont la

volonté n'a pas

28

à

être sondée, qui fait naître et mourir, dont, tout vient et à qui

tout aboutit.

Vécue

par le croyant, cette discipline contient en elle-même un germe de

la vie mystique. Si déjà la vie du simple fidèle est remplie du

sacré, combien plus le sera celle des hommes qui ont choisi de se

consacrer exclusivement au service de Dieu, qui, en plus de

l'accomplissement des obligations communes, s'imposent des pratiques

surrérogatoires et dont Dieu est la seule et unique pensée ! Déjà

le Coran mentionne des pratiques louables qui ne sont pas prescrites

à tout le monde. Les prières nocturnes ont dû jouer un grand rôle

dans la communauté primitive de Médine ; elles ne sont pas devenues

obligatoires, mais leur caractère d'oeuvres pies a toujours été

reconnu. Ces veillées nocturnes, tahajjud, seront pratiquées

avec prédilection par les mystiques.

La

prière rituelle elle-même recèle des virtualités dont les

mystiques n'ont pas manqué de tirer profit. Elle comporte bien un

minimum de récitation du Coran : la Fâtiha et trois versets

d'une autre sourate ; mais il n'y a pas de maximum, et le croyant

pieux peut réciter autant de texte sacré qu'il le peut. A cela

s'ajoute la pratique fréquente, dès les premiers temps de l'islam,

de la lecture en commun du Coran en dehors même de la prière. Lire

et réciter le Coran est, par excellence, une oeuvre pie et le mérite

en est grand : quelle prière saurait être comparée à la

récitation de la parole de Dieu ?

Pour

le croyant, le Coran est la parole de Dieu -- non pas un livre

inspiré comme la Bible, où l'on peut discuter de la validité de

tel ou tel passage, admettre ou contester l'attribution de tel livre

à tel auteur sacré, distinguer des genres littéraires et limiter

éventuellement la portée des récits historiques sans pour autant

manquer de foi. Le Coran est la parole de Dieu, il faut le prendre

tel qu'il est, en entier, sans distinction, même si l'on admet

ensuite que certains de ses versets en abrogent d'autres,

précédemment révélés.

C'est,

pour l'immense majorité de la communauté musulmane, une parole

incréée. Les mu’tazilites resteront à peu près isolés dans

leur tentative d'affirmer le contraire, et l'échec de la mihna

abbaside pour imposer par la force le dogme du Coran créé sonna le

glas de cette école. Pour les as’arites, l'épithète d'incréé

s'appliquera en propre au prototype céleste du Coran, à la Mère du

Livre (umm al-kitâb), consignée sur la Tablette bien gardée

(Law al-mahfûz), dont le Coran arabe est une traduction en

langage humain comme l'ont été, avant lui, la Bible, le Psautier et

l'Évangile. La position moyenne sera celle qui estimera que le texte

du Livre est incréé, mais que sa récitation ne l'est pas : « Ce

qui est écrit, appris par coeur ou récité est incréé, le fait

d'écrire, d'apprendre par coeur, de réciter est créé. » Mais les

plus intransigeants parmi les hanbalites iront plus loin : « Est

incréé tout ce qui se trouve entre les deux reliures », et toute

récitation du Coran est elle-même incréée. Le croyant qui récite

le livre sacré accomplit une action incréée de Dieu — ce qui

montre que, dès le départ, le problème de l'unicité de l'être ne

se pose pas en islam de la même façon que dans le christianisme.

On

ne lit pas le Coran comme on lit la Bible. Le but de la lecture n'est

pas de saisir le sens d'un récit

30

en

tant que tel, d'apprendre une histoire. Les récits sur les prophètes

d'autrefois qu'il contient ne veulent pas être des récits

historiques. Rapportés dans un but homilétique évident, ce sont

des paraboles où les péripéties des anciens prophètes permettent

de dégager une image type de l'expérience prophétique, image qui

permet de tirer un enseignement toujours valable et qui peut être

appliqué à la carrière de Muhammad. Même ici, il ne s'agit pas de

narration continue : ce sont de brefs éclairs, des rappels

d'événements apparemment connus, des allusions discrètes. Lues et

hautement estimées, les Vies des Prophètes, même celle du

Prophète de l'islam, n'ont jamais acquis une valeur canonique. Les

traditions prophétiques, non plus, ne sont pas des récits. On y

trouve bien, souvent, le rappel des circonstances qui ont amené le

Prophète à dire telle ou telle chose, la mention des personnages

qui étaient présents, mais l'intérêt est concentré sur la

sentence prononcée par le Prophète et qui porte sur tel point

litigieux de la loi ou de la doctrine ; l'événement décrit a la

valeur d'un précédent, les personnages nommés garantissent le

caractère authentique de la tradition. On n'attache pas d'importance

à l'anecdote racontée en elle-même.

Le

discontinu caractérise le style des sourates coraniques. L'attention

du croyant ne s'attache pas à une sourate comme unité formelle et

fermée, mais à des versets isolés qui expriment, avec une force et

une vigueur exceptionnelles, les thèmes de base de la prédication

coranique.

Les répétitions, les formules stéréotypées fatiguent celui qui

lit le Coran d'un jet ; elles permettent au croyant de mieux fixer

dans son esprit les vérités de sa foi, et les lui imposent avec

beaucoup de force. Composée d'éléments discontinus, révélée par

les éclairs solitaires des versets, l'image coranique de Dieu s'est

imposée au musulman. En récitant l'écriture sacrée, en

l'apprenant par coeur et en méditant sur ses versets, celui-ci croit

revivre, en partie, l'expérience du Prophète au moment de la

révélation.

Même

sans recourir à une exégèse symbolique, à la recherche du sens

spirituel caché, différent du sens littéral apparent, un passage

admet des explications divergentes selon les circonstances et la

situation où il est récité. D'autre part, entre plusieurs

interprétations possibles, un homme choisira celle qui correspond le

mieux à sa sensibilité et, très souvent, il aura recours au texte

sacré non pour s'en inspirer, mais pour justifier ses propres idées.

Compte

tenu de ces faits, il n'est pas douteux que le mysticisme islamique,

le soufisme, ne soit issu d'une méditation intense du Coran. Ce sont

les thèmes coraniques qui l'ont formé et qui lui ont donné le

cadre. Parmi ces thèmes, en premier lieu, l'image de Dieu, à jamais

ineffaçable : Dieu tout-puissant, qui fait ce qu'il veut. Rien ne

lui ressemble, et son essence ne peut être saisie. Il a créé le

monde de rien, et le monde périra : tout périra, sauf sa face. Tout

ce qui est sur terre passera, la face de Dieu, Puissant et

Majestueux, restera. Il a fait naître l'homme, le fera mourir et le

ressuscitera une autre fois. Au son de la trompette, les morts

surgiront et seront jugés. Ce jour-là, rien ne sera d'aucune

utilité à l'homme, ni les biens ni les enfants, il sera seul à la

face de son Juge. Car ce jour-là, à qui appartiendra le pouvoir ? A

Dieu, l'unique, le Tout-Puissant. Ceux qui ont

32

établi

un autre dieu à côté de Dieu seront jetés dans la Géhenne, et la

Géhenne gémira : « En avez-vous encore ? » Il ne leur servira à

rien de dire qu'ils n'avaient pas su. Car, le jour où fut créé

Adam, Dieu tira de ses reins la semence de tous ses descendants pour

leur poser la question: « Ne suis-je pas votre Seigneur ? »

(a-lastu bi-rabbikum). Ils répondirent : « Si ». Ils sont

ainsi tous engagés par ce Covenant primordial, et leurs excuses

n'ont pas de sens. Mais, d'autre part, s'ils n'ont pas cru, c'est que

Dieu les a induits en erreur et a scellé leurs coeurs avec de la

cire. Il est Celui qui guide et Celui qui laisse errer. Il est

également plein de miséricorde. A ceux qui l'ont craint, qui se

sont présentés le coeur contrit, Il dira d'entrer en paix au

Paradis ; ils y auront tout ce qu'ils désirent, et Dieu leur en

réserve plus encore (mazîd).

Soumis

à la réflexion rationnelle, le Coran présente un certain nombre

d'apories, notamment en ce qui concerne le problème de la

prédestination et du libre arbitre, de la toute-puissance divine et

de la responsabilité de l'homme. Inlassablement, le Coran affirme

cette dernière ; mais ailleurs, tout aussi fréquemment, il déclare

que rien ne se passe sans la volonté de Dieu, que l'obstination même

des pécheurs vient de Dieu. Dans une expérience religieuse

authentique, le sentiment de la dépendance absolue de la divinité

coexiste avec celui de la responsabilité morale des actes, et ils

n'apparaissent pas comme contradictoires ; il est plus difficile de

les concilier dans une réflexion théologique construite selon des

critères rationnels. Les différentes écoles islamiques adopteront

des solutions différentes, ce qui ne manquera pas d'exercer une

influence sur l'orientation des écoles mystiques. Les ascètes des

premiers siècles de l'hégire vivent dans la crainte perpétuelle du

jugement divin. A la même époque, les mutazilites soulignent le

libre arbitre humain, la justice absolue de Dieu qui ne peut faire ce

qui est injuste. L'homme est donc pleinement responsable de ses actes

et assume cette responsabilité avec gravité ; mais il ne peut

jamais savoir s'il a satisfait la volonté divine, si ses fautes ne

l'emportent pas sur ses mérites, s'il n'est pas voué à la

damnation éternelle. Plus tard, on sera plus confiant. Ach’arites

et hanbalites souligneront la puissance absolue de Dieu, créateur

des actes humains. Cette doctrine a inspiré une attitude d'abandon

confiant à la volonté divine joint à la certitude du salut futur

par le fait même de l'appartenance à la communauté élue. Tandis

que la première conception favorisait une métaphysique dualiste où

Dieu et la créature étaient radicalement différents, la seconde

pousse vers des solutions monistes. C'est là bien entendu, une

simplification ; en réalité, le développement fut bien plus

complexe et plus nuancé.

L'accomplissement

ponctuel des prescriptions religieuses suffit à sauver un homme du

feu de l'enfer. Le mystique, lui, n'aspire qu'à Dieu. Cette

aspiration s'exprime très souvent à l'aide d'une image coranique

que nous venons de mentionner, celle du « jour du surcroît »,

yaum al-mazîd : pour ses proches, Dieu a plus que les joies

du Paradis. L'essence divine se révélera ce jour-là à Ses élus,

elle les saluera et les conduira hors du paradis commun. Répandu dès

les premiers siècles de l'islam, chanté notamment par

34

Dhû'l-Nûn

l'Égyptien et Muhâsibî, ce thème s'enrichira et se transformera

avec le temps. Le plus souvent, il sera question de la taverne

mystique où l'Aimé apparaît sous les traits d'un jeune échanson,

ce qui donnera aux poètes arabes et persans une occasion de chanter

l'amour pour l'homme beau, reflet de la beauté divine. D'autres

fois, l'image primitive sera préservée plus fidèlement. Le cas le

plus notable est celui de la danse des Mevlevis, les célèbres «

derviches tourneurs ».

Une

autre image d'origine coranique qui aura la prédilection des soufis

est celle du Covenant primordial. L'extase mystique devient le rappel

ou plutôt la réactualisation de cet événement. Sorti du sommeil

dans lequel l'a plongé sa condition charnelle, le derviche se

rappelle ses origines véritables et renouvelle son adhésion à Son

Seigneur. Ici encore, l'image a eu son prolongement « liturgique »

: l'action de la musique sur l'homme, telle qu'elle se manifeste

notamment dans les séances de samâ' , est expliquée par le

souvenir de cet événement. Toute voix est censée reproduire le

premier appel et susciter, dans l'âme, les mêmes résonances. Le

derviche entre en extase mû par le désir de retrouver sa condition

initiale, de contempler la beauté divine. Ce rappel lui fait faire

des mouvements, l'amène à danser. Le samâ' n'est point un

moyen artificiel de provoquer l'extase, mais un rite qui permet de

réactualiser un état antérieur au temps. Il n'est pas étonnant

que le samâ' soit interprété également comme évoquant la

parole créatrice, Kun ! (Sois !), par laquelle toutes

choses sont venues à l'existence.

La

réflexion des soufis s'emparera de l'image et la développera. Le

jour du Covenant, les hommes n'étaient pas encore nés. Quel était

alors leur mode d'existence ? Comment ont-ils pu témoigner ? La

vieille représentation de la préexistence des âmes s'insinue dans

l'esprit. Plus nuancé, un Junaid parlera de l'existence des hommes

en Dieu. N'ayant pas encore d'existence autonome, ils n'étaient que

l'objet de la science de Dieu. Celui-ci le fit exister, leur posa la

question, attesta pour eux. Pourtant, cet état premier était un

genre d'existence plus vrai et meilleur que celui que les hommes ont

acquis par la création. Au bout de son cheminement, le mystique le

retrouvera. S'étant dépouillé de son humanité, il ne vivra que

par Dieu et en Dieu.

Ainsi,

la réflexion sur un verset coranique ouvre la voie aux idées

néo-platoniciennes. Cela ne veut pas dire que la doctrine soufie

sera une copie de cette philosophie, mais seulement que des problèmes

posés par la méditation du Livre seront très souvent formulés en

termes empruntés au néo-platonisme et les solutions adoptées

analogues aux siennes. Il est difficile de faire le départ entre

l'apport étranger et la réflexion sur les données coraniques et de

tracer les limites exactes entre les deux dans chaque cas

particulier. Comme dans l'exemple étudié, il y a souvent rencontre

des thèmes et des images et il paraît plus indiqué de parler de

symbiose que d'influence. En tout cas, certains domaines resteront

toujours plus réfractaires ; même lorsqu'elle est définie en

termes philosophiques, l'image de la Divinité restera toujours

profondément coranique.

Le

soufisme est né dans une atmosphère de profonde imprégnation

coranique. Mais d'autres mou-

36

vements

islamiques -- tel le hanbalisme -- en étaient également sortis,

sans que pour cela ils aient évolué dans un sens analogue. A

l'appel initial du texte sacré, certains individus réagissaient

d'une façon spéciale qui était conforme à leurs aspirations

profondes.

L'imitation

du Prophète, l'obligation de suivre sa sunna en toute

circonstance, est un trait caractéristique de l'islam. Les soufis,

surtout dans les premiers siècles, se distinguent par une

observation particulièrement scrupuleuse de la sunna ; ils

insistent sur certains aspects de l'expérience du Prophète, sa

pauvreté initiale, les longues persécutions qu'il a subies dans sa

ville natale, la soif du divin qu'il éprouvait en s'isolant dans les

montagnes de Hirâ, sa rencontre avec Gabriel qui lui révéla sa

vocation prophétique et lui dicta les premières paroles du Coran,

ses jeûnes, ses prières, son combat. Mais l'épisode de la vie de

Muhammad qui a sans doute le plus influencé les mystiques fut celui

de son voyage nocturne : une nuit il fut ravi de la Mosquée Sacrée

à la Mosquée Très-Lointaine, de La Mecque à Jérusalem, et de là

au ciel. On trouva des allusions à ce voyage dans deux sourates du

Coran, 17, 1 : « Gloire à Celui qui transporta la nuit Son

serviteur de la Mosquée Sacrée à la Mosquée Très-Éloignée... »

et plus encore dans les premiers versets de la sourate 53 qui

décrivent une vision du Prophète. Monté au septième ciel, ce

dernier s'approcha de la Divinité « de deux arcs ou moins » (qâba

qausaini au adnâ), et il l'a vue « près du Lotus de la Limite

(sidrat al-muntahâ), à côté duquel se trouve le jardin

al-Ma' wa ». Les récits de cette ascension nocturne

(al-mi`râg), très nombreux, formeront la piété musulmane.

Pour les mystiques, l'ascension du Prophète constitue le modèle de

leur propre expérience extatique. Elle marque en même temps ses

limites ; l'essence divine reste inaccessible, le qâba qausain

est le maximum de ce qu'un homme peut atteindre, car personne ne

saurait dépasser le Prophète.

A

d'autres égards encore, l'imitation de Muhammad informe la mystique

musulmane. Bien que la femme ne jouisse pas d'une haute opinion et

que sa fréquentation soit considérée comme occasion de péchés,

très peu nombreux seront les soufis qui pratiqueront le célibat, et

moins encore ceux qui le prêcheront pour les autres. Comme tout

musulman, le mystique doit se marier et contribuer ainsi au

renforcement de la communauté. Le soufi n'est pas un moine, il vit

au milieu de ses semblables et partage leur vie, leurs joies et leurs

peines.

Or,

c'est comme un ascétisme que commence le mysticisme islamique. Il

s'agit d'une piété pratique qui ne s'embarrasse pas encore de

spéculations métaphysiques, qui prêche la primauté de l'intention

sur l'acte, qui met l'accent sur la pureté intérieure, la

contrition, la crainte de Dieu. La note dominante est pessimiste. Un

homme ne sait jamais comment il affrontera le jugement divin, il

ignore s'il n'est pas voué à la damnation éternelle. Cette vie

périssable est sans valeur, chaque jour nous rapproche de la mort.

Il ne faut pas s'attacher à ce monde-ci, Dieu lui-même le déteste

; il n'a de valeur que comme préparation à l'au-delà, mais on ne

peut jamais être sûr que la foi et les oeuvres accomplies nous

préservent de la colère divine. On ne doit pas rire, pleurer

convient

38

davantage

au pénitent. Renoncer aux biens de ce monde est recommandé, non

comme un but en soi, mais parce que leur usage détourne de l'amour

de l'autre monde.

Parmi

les compagnons du Prophète on cite quelques cas d'ascètes, tels Abu

Dharr al-Ghiffârî ou ‘Imrâm b. al-Husain al-Khuzâ’î. Ce

n'est cependant pas sur eux qu'insiste la tradition hagiographique.

Elle parle d'un groupe de dévots désignés comme ahl al-suffa «

les gens de la banquette » qui se seraient adonnés à des pratiques

ascétiques et à des exercices surérogatoires à la mosquée de

Médine ; et elle mentionne avec prédilection la légende de ‘Uwais

al-Qaranî, qui est très importante pour la compréhension de

certaines tendances du mysticisme islamique et sur laquelle nous

reviendrons. Les hagiographes aiment à revenir également sur la

piété des quatre premiers califes qui, notamment Abd Bakr et ‘Ali,

auraient joué un grand rôle dans la transmission de la science

mystique.

Dans

la seconde moitié du Ier siècle de l'hégire, le nombre

d'ascètes croît, non seulement à Médine, en Syrie ou en Irak,

mais aussi dans le Khurâsân qui forme alors la marche orientale de

l'empire des califes. Parmi ces ascètes, quelques noms se détachent

de la masse, en premier lieu celui de Hasan de Basra, en qui les

soufis verront plus tard leur patriarche.

Né

en 21 de l'hégire, probablement à Médine, il passe la plus grande

partie de sa vie à Basra, où il meurt en 110. Sa personnalité eut

une influence considérable dans tous les domaines de la pensée

islamique. Prêchant l'imminence de la mort et du jugement, la

nécessité de conformer les actions et les paroles, les pensées et

les actes, il insiste sur l'importance de l'examen de conscience et

sur le devoir de correction fraternelle. Correction fraternelle mais

non insurrection armée : il refuse de prendre parti dans les

querelles intestines qui, de son vivant, déchirent la communauté

islamique. Dans la question si importante de la prédestination et du

libre arbitre, il occupe une position intermédiaire, et les

partisans des deux solutions le revendiqueront. Il est ascète, mais

ne préconise pas l'abstinence sexuelle et sa cuisine non plus n'est

pas dépourvue d'attrait. Le juste gain est considéré par lui comme

légitime, et l'argent n'est pas répudié : seulement il entend se

contenter, pour sa part, de l'indispensable, et distribuer le reste.

Tous

ces traits resteront caractéristiques du mysticisme islamique. Le

soufi vit dans le siècle, son existence n'a de sens que parce qu'il

appelle les autres à Dieu et les fait bénéficier de son intimité

avec Dieu.

Mentionnons

quelques autres ascètes des premiers siècles : ‘Abd al-Wâhid ibn

Zaid, organisateur et fondateur du cloître d'Abâdân ; Ibrâhim ibn

Adham, prince de Balkh, dont le récit de la conversion est influencé

par la légende du Bouddha ; la grande sainte Rabi'a al-’Adawîya,

et Abû Sulaimân al-Dârânî. Les tendances au renoncement,

l'attachement scrupuleux à la Loi, se combinent chez ces ascètes

avec un sens très profond de la pureté intérieure et un amour

passionné de Dieu.

La

Loi islamique considère un certain nombre d'aliments comme impurs :

la viande du porc, le sang, etc. Ces interdits sont observés par les

soufis ; ils en ajoutent d'autres, qui ne sont pas sans rappeler

40

des

usages courants parmi les anciens chrétiens. Toute nourriture

acquise d'une façon illicite est impure ; tout ce qui est acheté

avec de l'argent gagné dans des jeux de hasard, par la rapine, par

le mensonge, est impropre à la consommation. On ne mange pas ce qui

n'a pas été donné de bon coeur, et très souvent on considérera

comme impur tout ce qui vient des puissants de ce monde, émirs et

rois, parce que leurs biens sont acquis de façon illicite, que leur

pouvoir est usurpé et qu'ils sont des « tyrans ». A la limite,

tout aliment acheté au marché est suspect, on n'a confiance que

dans la nourriture qu'on a préparée soi-même. La nourriture licite

a une vertu propre, sa consommation rapproche le fidèle de Dieu. Au

contraire, les aliments impurs rendent l'homme plus animal,

l'abaissent et l'induisent au péché.

Voici

quelques exemples de cette attitude, empruntés à la littérature

soufie plus récente, mais tout à fait conformes à la tradition.

Dans

les débuts de sa carrière, le Khwâga Bahâ' al-Dîn Naqsband (XIVe

siècle) fut reçu, un soir, par le roi de Hérat. Ce dernier

avait pris des précautions pour que la nourriture servie fût

rituellement pure. Le saint homme n'y toucha point : c'était un

repas offert par un roi, donc irrémédiablement impur.

Son

contemporain, ‘Alî-i Hamadânî, tomba en extase dans les débuts

de sa carrière. Son état mystique fut tellement fort qu'il fallut

le lier pour qu'il se tînt tranquille. Finalement, on acheta de la

nourriture au marché: elle n'était plus absolument pure et sa

consommation par le mystique interrompit son extase et le ramena à

son état normal.

41

Le

moindre manquement à la pureté a ainsi pour effet d'éloigner

l'homme de Dieu et de le réduire à son niveau humain. De ce point

de vue, le dernier récit cité est comparable à cet autre que l'on

rapporte d'un cheikh anonyme. Un jour, après des années d'exercices

ascétiques et d'efforts, ce dernier atteignait la lumière sans

borne et sans limite qui remplit le monde et constitue sa véritable

essence. Il resta stupéfié et terrassé, et ne put ni manger ni

dormir. Il ne sut comment retrouver son état normal. Un ami lui

conseilla de soulever, dans un champ, un brin de paille sans la

permission du propriétaire. Le cheikh le fit, la lumière disparut

et il revint à lui.

L'amour

de Dieu est une des notes dominantes de cette mystique. C'est aussi

un de ses traits qui scandalisent le plus les docteurs. Étant donné

la transcendance absolue de Dieu et son incommensurabilité avec les

créatures, il leur paraît scandaleux d'envisager leurs rapports en

termes érotiques. Toute la mystique postérieure emploiera un

vocabulaire érotique et parlera de Dieu comme du Bien-Aimé et des

mystiques comme de ses amants. La poésie soufie popularisera ces

images qui constitueront un thème de prédilection de poètes

persans, turcs ou urdu. Bien que, dans les premiers siècles, on soit

encore loin de cette rhétorique, certains aspects de cet amour sont,

par contre, déjà présents.

De

cet amour, Dieu est le seul et l'unique objet. On le désire pour

lui-même, indépendamment de la récompense qu'il peut donner. On

connaît les paroles célèbres de Rabi’a sur les deux amours,

l'amour qui implique son propre bonheur — par la jouissance de Dieu

— et celui qui est vraiment digne de Lui, où

42

elle-même

n'a plus de part. Des idées analogues se trouvent formulées dans un

hadîth : « Ce monde-ci est interdit, aux hommes de l'autre monde ;

et l'autre monde est interdit aux hommes de ce monde-ci ; et ils sont

tous les deux interdits aux hommes de Dieu Très-Haut. » Ni

jouissance des biens de ce monde, ni de ceux de l'autre, mais

dévotion exclusive pour Dieu. Même malgré lui, voire contre son

ordre.

Abû

Sulaimân al-Dârânî dit : « Mon Seigneur ! Si Tu m'as réclamé

mes pensées secrètes, je t'ai réclamé Ton Unicité ; et si Tu

m'as réclamé mes péchés, je T'ai réclamé Ta générosité ; et

si Tu m'a mis parmi les gens de l'enfer, j'ai proclamé aux gens de

l'enfer mon amour pour Toi. »

L'amant

mystique se sent rejeté par son Bien-Aimé, mais il continue à lui

témoigner son amour. Un peu plus tard, cette attitude se

cristallisera dans un symbole qu'affecteront les plus grands parmi

les soufis, depuis al-Hallâg jusqu'à Ibn ‘Arabi : la

réhabilitation d'Iblîs.

On

connaît la version coranique du récit de la chute des anges. Ayant

créé Adam, Dieu exige des anges qu'ils se prosternent devant lui.

Iblîs n'obéit pas, est rejeté et devient démon. Mais pourquoi

Iblîs ne s'est-il pas prosterné ? Les mystiques savent la réponse

: il refusa d'adorer un être créé.

Contre l'ordre formel de Dieu, il témoigna de l'unité divine. Dans

sa réjection, il reste le parfait monothéiste. Il a enfreint un

ordre de Dieu, non sa volonté. Il reste le modèle de l'amant de

Dieu.

Certains

en ajoutent un autre : le Pharaon de l'exode. En refusant d'obéir à

Moïse, celui-ci n'a fait que récuser un intermédiaire créé entre

Dieu et lui-même.

Ces

sommets de spéculation sont rarement atteints dans les deux premiers

siècles. Plus fréquente est encore l'attitude classique qui oppose

ce monde-ci et l'autre, l'infinie majesté divine et le peu de valeur

de l'homme, l'obligation pour celui-ci d'accomplir les devoirs

prescrits sans s'attendre à une récompense, Dieu est souverain, il

agit comme il veut et donne ce qu'il veut et à qui il veut. Ahmad b.

‘Asîm al-Antakî dit : « Estime grandement le peu de subsistance

que Dieu t'a donné, pour que tes remerciements soient purifiés ; et

estime comme peu de choses les nombreux actes d'obéissance envers

Dieu que tu pratiques en meurtrissant ton âme et l'exposant au

pardon. »

L'accomplissement

des devoirs et des actions surérogatoires rapproche l'homme de Dieu

; c'est même la seule voie qui conduise vers lui. Dans un hadîth

qudsi célèbre, attesté pour la première fois au

IIIe siècle de l'hégire, mais sans doute plus ancien,

Dieu dit : « En vérité, les hommes ne se rapprochent de moi que

par des oeuvres semblables à celles qui leur ont été prescrites.

Et le serviteur ne cesse pas de se rapprocher de moi par des oeuvres

surérogatoires jusqu'à ce que je l'ai pris en affection. Et lorsque

je l'ai pris en affection, je suis devenu sa vue, son ouïe, sa main

et sa langue : c'est par moi qu'il entend, c'est par moi qu'il voit,

c'est par moi qu'il touche, c'est par moi qu'il parle. » Par des

oeuvres de dévotion, l'homme se rapproche ainsi de Dieu. A un

moment, il rencontre l'amour de Dieu qui vient au-devant de lui. Il

perd alors ses qualités humaines, Dieu remplit tout son être et il

n'existe plus qu'en Dieu.

Le

mépris de ce monde entraîne celui de la science

44

profane,

voire de toute science qui ne soit pas celle de Dieu. Antakî affirme

: « En vérité, j'ai étudié les sciences, j'ai éprouvé les

principes, j'ai goûté la pensée, j'ai absorbé la théorie, je me

suis efforcé de retenir en mémoire, je me suis plongé dans la

sagesse, j'ai appris l'art sermonnaire, j'ai coordonné la parole

avec la pensée, j'ai fait correspondre l'expression et le sentiment,

mais je n'ai trouvé aucune science plus riche en connaissance, plus

guérisseuse pour la poitrine, plus pieuse dans ses intentions, plus

vivifiante pour le coeur, plus attirante au bien et plus répugnante

au mal, plus dominante au coeur et plus nécessaire au serviteur que

la science de la connaissance (ma'rifa) de l'Adoré, de la

profession de son Unité (tawhid), de la foi et la certitude

de son au-delà, afin que s'établissent sûrement la crainte de son